A Cunty Carnival: Judy Chicago and the Construction of Feminist Community

Judy Chicago Part 2/3

A Cunty Carnival: Judy Chicago and the Construction of Feminist Community

I’ve often wondered if I’d had more teachers willing to toss around a well-placed c-word, I’d have spent less time in study hall, thinking about how to shorten my uniform skirts without getting caught instead of doing my math homework. “A male looks at an image of a cunt and reacts with his socially conditioned feelings about women,” wrote Judy Chicago in 1971, the year after she founded the Feminist Art Project, the first women's arts program, at Fresno State College. “I started the Feminist Art Program in Fresno because, as a result of my own struggle, I suspected that the reason women had trouble realizing themselves as artists was related to their conditioning as women,” she explained. Things might have been different if I had teachers like that.

In 1970, when Judy took a teaching job at Fresno State, she’d never heard of it, but that didn’t matter. The chair of the Art Department had basically explained that she could do whatever she wanted, and he seemed excited that Chicago wanted to teach a class for women only. They’d both noticed that while many young women entered beginning art classes, few emerged and became professionals—the metrics of success didn’t match those of their male colleagues. So Judy put up signs in the hallways, asking female students to meet with her and help put together a curriculum. Eventually, she gathered 15 willing participants, and started holding classes—meetings, really, but off-site, away from any men, and with a flexible syllabus. They ended up mostly talking: about their relationships, their sex lives, and the way that men made them feel. There were classes devoted to how often they were harassed on the street, catcalled, and made to feel unsafe. There were classes devoted to how they dealt with their boyfriends. Their homework included making art, in any media, dealing with the sensation of being physically invaded by a man. By the end of the first semester, Miriam Schapiro, a Canadian-born painter Judy admired and who taught at a newly-established school called CalArts (soon to be known as a seedbed of the conceptual and environmental art movements, it was, interestingly, co-founded by Walt Disney), had joined Judy as a co-professor, and they used Miriam’s CalArts connection to start to collate an archive there of the names of women artists—long ignored and marginalized.

In the summer of 1971, after the first year of their Fresno program, Judy and Miriam, along with Dextra Frankel, a professor at California State University, spent a month touring the west coast looking for pieces for a women’s art show. The three curators would, by word of mouth, find women artists to visit in their car, highlighting what Chicago found to be an essential problem: there was no centralized union, group, or sisterhood by which women artists could find other women artists, research the history of women artists, or be matched with the support structures like grant programs, teaching and learning opportunities, spaces to exhibit their work or even, simply, formalized networks by which they could meet and talk to other women artists. At the end of their tour—after seeing more than fifty studios—Chicago concluded that feminism needed to be cultivated with the creation of a feminist community: The majority of the women that Chicago, Schapiro and Frankel encountered were self-taught, working from tiny spaces in their own homes, next to laundry or cleaning supplies or other detritus of their domestic duties—a far cry from the resources of most male artists. The next step towards building the dream world, one where women would have the same opportunities as their male counterparts, Chicago figured, was to start a feminist teaching program at a respected university. So when CalArts called, offering resources for the Feminist Arts Project to move there in the fall of 1971, Judy accepted, bringing eight students from Fresno with her. She and Miriam called this new version of their class the Feminist Arts Program. “Twenty-one young women artists elected to join this exclusively female class. We do not teach by fixed authoritarian rules,” wrote Schapiro. She went on to describe how the students began class sitting in a circle, allowing discussion to flow from person to person, without the hierarchy of a traditional college classroom wherein the professor-student power dynamic was evident in lecture and seminar-style teaching.

Womanhouse, The Feminist Arts Program, and the progressive academic objectives of Schapiro and Chicago helped establish a 1970s Los Angeles that could become an unlikely international seat of feminist theory and art making.

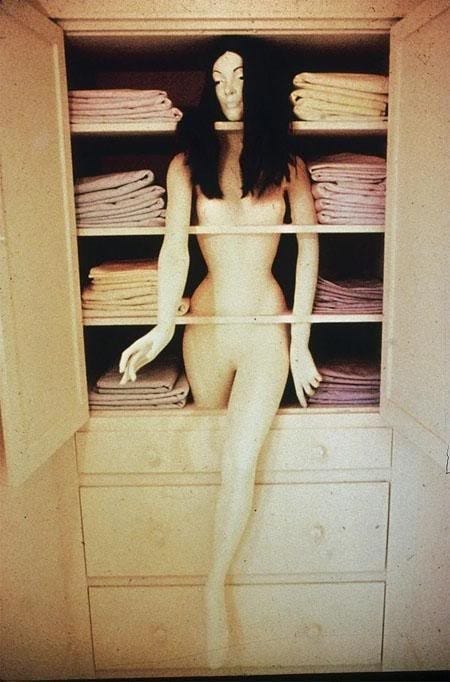

The first class project these twenty-one students embarked on was Womanhouse, 1972. Taking over a dilapidated seventeen-room mansion in Hollywood, twenty-eight artists (including some friends of Schapiro and Chicago who weren’t technically their students, and including Schapiro and Chicago themselves) demolished, reconstructed, and refurbished the home, turning each room into an environment attempting to “concretize the fantasies and oppressions of women’s experience,” described Lucy Lippard. “It included a dollhouse room, a menstruation bathroom, a bridal staircase, a nude womannequin emerging from a (linen) closet, a pink kitchen with fried-egg-breast decor, and an elaborate bedroom in which a seated woman perpetually made herself up and brushed her hair.” The living room was saved for performances where women enacted births or engaged in mundane domestic tasks like ironing.

Sandy Orgel, Linen Closet, 1972, Womanhouse project

“There are some interesting unwritten laws about what is considered appropriate subject matter for art making,” wrote Schapiro. “Womanhouse reversed these laws. What formerly was considered trivial was heightened to the level of serious art-making.” The elevation of domestic craft to high art would remain a hallmark of feminist art.

“Women had embedded in houses for centuries and had quilted, sewed, baked, cooked, decorated and nested their creative energies away,” Chicago wrote in her autobiography. “What would happen, we wondered, if women took those same homemaking activities and carried them to fantasy proportions?” Would the female makers of Womanhouse be respected as real artists, which, despite the laboriousness, skill requirements and usefulness of their output, they had never been considered?

Vickie Hodgetts, Robin Weltsch, and Susan Frazier. Nurturant Kitchen at Womanhouse, 1972.

The critics were mixed, some deriding the installation as therapy, not art; others ignoring the entire endeavor. There were, despite the haters, people fascinated by what these women created. Not only was the project reviewed in Time Magazine, but ten thousand people came to see Womanhouse in the single month it was on view. Its success gave Judy Chicago the energy and impetus to pursue an even grander collaborative work, The Dinner Party, which was shown later in the decade and will be the subject of next week’s newsletter. Unfortunately, Womanhouse was not preserved, cared for, or institutionally acquired, so all we have are old photos and videos.

The elevation of domestic craft to high art would remain a hallmark of feminist art.

Womanhouse, The Feminist Arts Program, and the progressive academic objectives of Schapiro and Chicago helped establish a 1970s Los Angeles that could become an unlikely international seat of feminist theory and art making. The late 60s focus on Civil Rights and anti-war movements in America and their accompanying protests were inspired in part by the uprisings across Europe in 1968 (the student movements in May in Paris, Solidarnosc in Poland, The Prague Spring in Czechoslovakia), which themselves had found kindling in European postmodernist texts like de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex, Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle, and Foucault’s The Order of Things. When these texts arrived in America in the 1970s via translation, instructing a new continent to question the rules and realities by which culture and society had long been governed, they mixed together in California with an LA-specific spirit of discovery and experimentation exemplified by Disney, the space program, drug culture, and even Scientology. It was this cultural milieu that, despite the deeply patriarchal and male-centric art world hierarchy, allowed for the 1973 opening of the Woman’s Building, a multi-use space that hosted educational programs in different art media as well as programming concerning the development of womens’ identity, studio spaces for rent, community activist meetings and development opportunities, a feminist bookstore, a coffeehouse, and more.

Next week we’ll take one final look at Judy Chicago and what is perhaps her greatest legacy, The Dinner Party. If you’ve signed up for my VIP newsletters, you’ll also receive a detailed walk-through and review of her survey show at the New Museum, which up through January.

I love you Sarah thank you for these offerings.