In seventh grade I had a special Lisa Frank diary that I used to record quotes that inspired me, including my favorite lines from Clueless and several Rumi poems, as well as all the intel I could find about the modern dance pioneer Isadora Duncan, who died when her scarf was caught under the wheel of a convertible in the South of France. I’m sure you’ve heard that Michelangelo quote, I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free. That one was perhaps my favorite of all the things I wrote in that little book, and years later, when I went to Europe and saw the layered garments and veils of the Virgin Mary in his Pieta, and the curling pubic hair of his David, I got how magical that carving skill really was. How it was almost alchemy that he could take a big block of rock and chip away at it until he revealed some astonishing figure that had been in there all along.

Eleanor Antin (Fineman), born in the Bronx in 1935 to Jewish parents who had recently immigrated to America from Poland, had probably also heard that quote while studying art and writing at the City College of New York. It was while in school that she met her husband, art critic and writer David Antin, and when he was offered a job to run the art gallery at UC San Diego in 1968, the two uprooted their one-year-old son and moved to Solana Beach. The move forced Antin to give up some of her professional aspirations, which had included acting. But she stayed focused on performance and art making, inspired by the Dada artists of the post-WWI era, as well as the Fluxus art movement (remember their “Vice President,” Shigeko Kubota?). Her work involved inhabiting different characters and making works that explored identity as a construct. She also taught, the primary avenue open to female artists of the 60s and 70s, at both UC Irvine and UC San Diego.

In 1972, Antin was invited to submit work to the Whitney Biennial, a large-scale art exhibit mounted every-other year (since 1932) at the famed Whitney Museum of American Art. An important exhibit that is visited by thousands and has historically been able to launch an artist’s career, the institution limited its submissions to painting and sculpture, ignoring other media like film and video and performance.

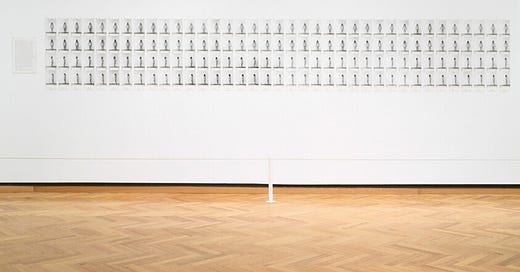

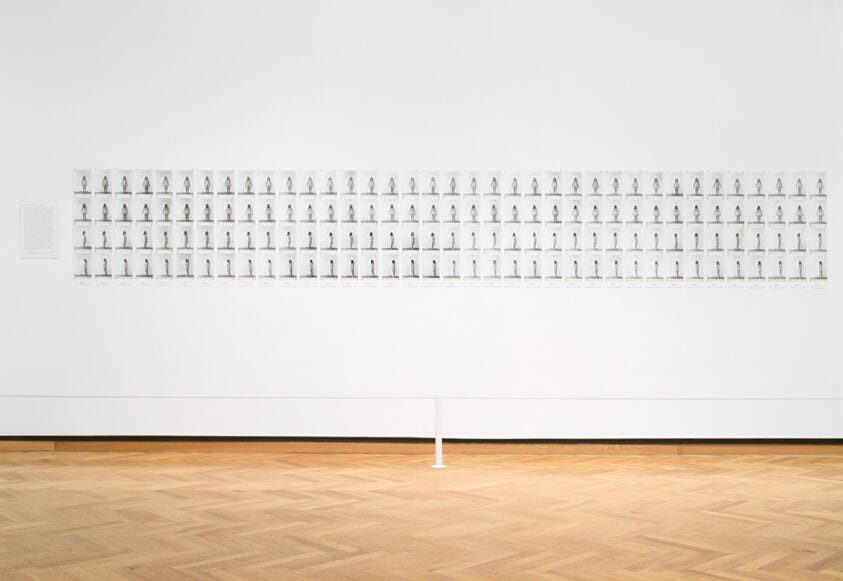

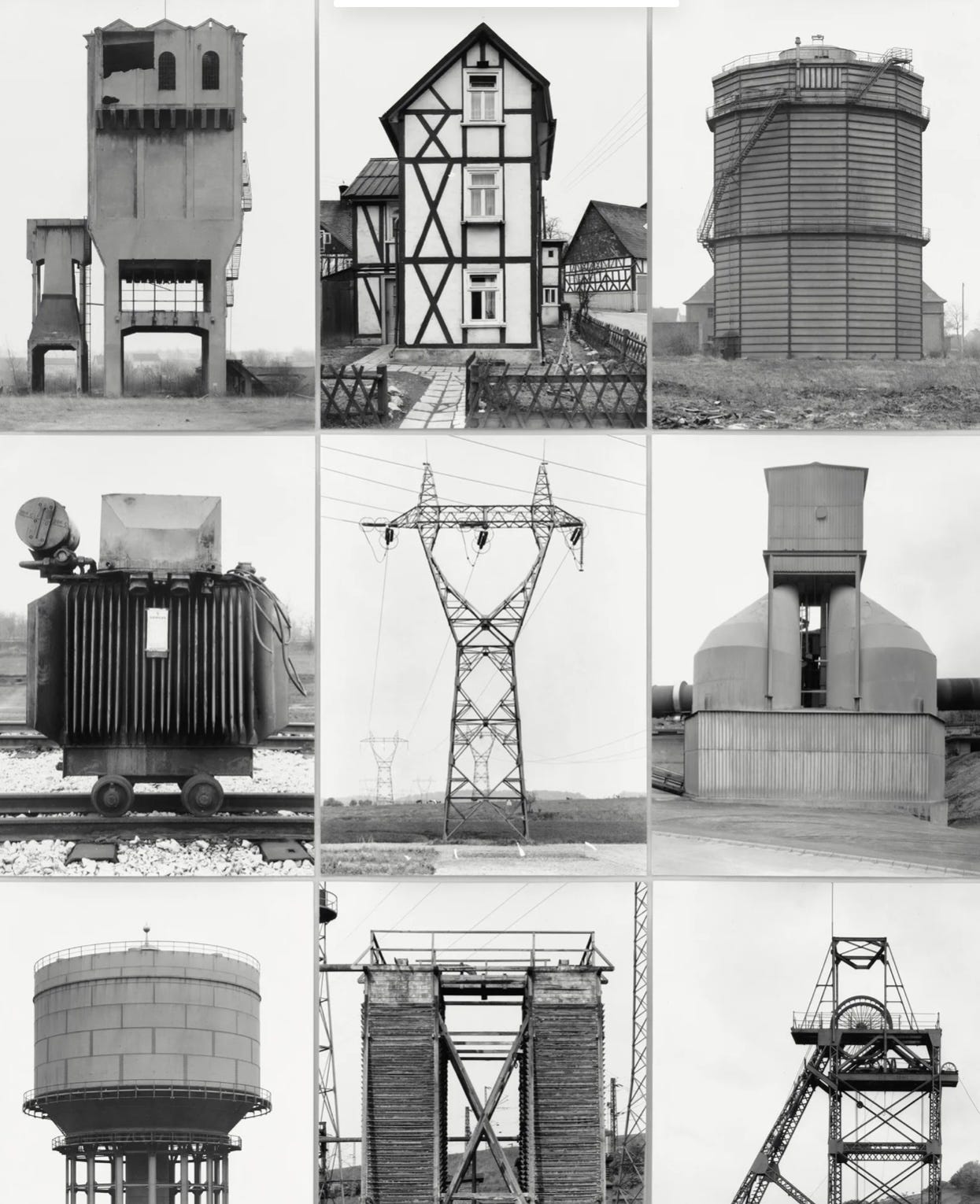

For her project, Antin decided to document in photography her own body as she metaphorically carved away at it, a play on Michelangelo’s mythologizing of his own abilities: over 37 days, Antin took pictures of herself from four identical angles as she adhered to a rigid crash diet prescribed in a popular Womens’ magazine. Carving: A Traditional Sculpture utilizes the documentary-style photography of Bernd and Hilla Becher, important German photographers who founded the Düsseldorf School of photography and made work based in the practice of typology, the study and classification of object types, in order to study the industrialized architecture of Western Europe that had defined the modern era. Like the Becher’s, Antin’s work classifies her photographic evidence in organized groupings, series of images organized in 37 columns, representing each day of her diet, and 4 rows, each holding a singular view of her body. Below the works she incorporates text describing the project, a co-mingling of media also utilized by the pioneering Becher’s (the mix of text and photography was a hallmark of conceptual art). In this way, she both pokes fun at the traditions of art—the patriarchal institutions that had long upheld the idea of male-artist-as-genius, carving away at his marble block—and humanizes the serialism and documentary aspects of Minimalist Art. Antin turned the cold clinicalism of simplified forms such as the grid into a personal commentary on society’s expectations of the female body and the role of women, who usually, as the subject of most of art in our modern history, are depicted as idealized forms, not as real people on a diet. By the way, Carving: A Traditional Sculpture, was considered too conceptual to be sculpture and was rejected from the Biennial, though Antin would go on, a year later, to show another important work at MoMA, 100 Boots. She has had solo exhibitions at the Hirshhorn Museum, MOCA Los Angeles, and Kunsthalle Wien, and at 88 years old, is still an important figure in the feminist art movement.

I loved this one! Thank you.

You are amazing Thank you Sarah!!! Happy Holidays to you and your family