I became fascinated with the ability of art to document the time, place, and cultural identity of the artist. How could I, as an African American woman artist, document what was happening around me? —Faith Ringgold

Though the Pattern and Decoration movement did not explicitly include Faith Ringgold in its ranks, historical revision has softly welcomed her into its orbit thanks to her work in quilting, appliqué, colorful geometry and references to diverse sources like Tibetan thangka and African Kuba cloth. Born in 1930 in Harlem-the height of the neighborhood’s Renaissance—to an accomplished seamstress-designer mother, Willi, and a father who was, among other things, a minster, Ringgold grew up drawing and crafting on days she couldn’t make it to school because of her chronic asthma. The cultural milieu of her block alone would have encouraged her creativity; Langston Hughes lived just around the corner, Sonny Rollins was her childhood friend and would practice saxophone at her parents’ parties. Her family encouraged her to attend City College in New York to study art, but as majors for women were very limited, she was only allowed to study arts education. After graduating she taught art in public schools while continuing her private artistic practice.

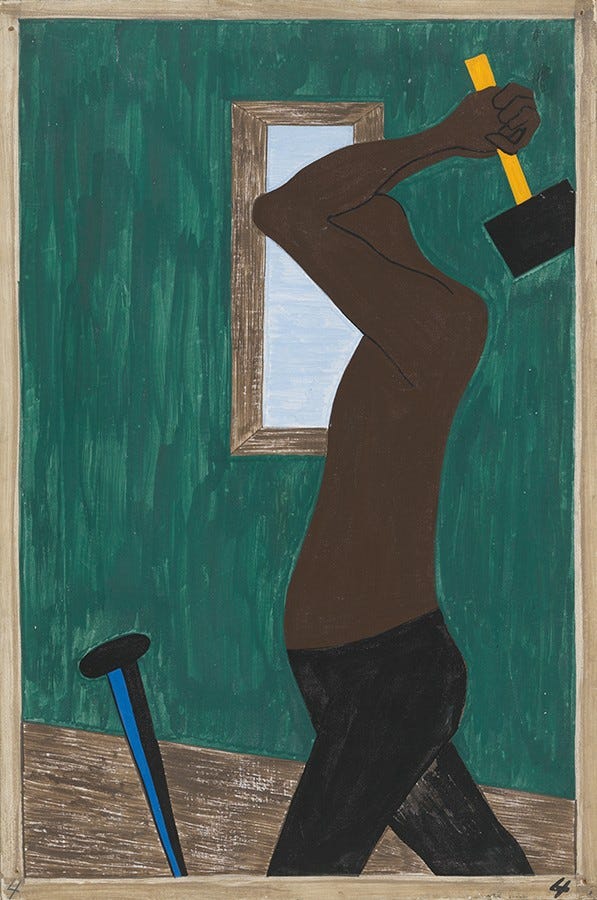

In the 50s, Ringgold married a jazz musician, had two kids with him, and filed for divorce within a few years because of his addiction issues. She graduated from an MA program in 1959, and left for Europe to tour with her mom and sisters. I got a fabulous education in art - wonderful teachers who taught me everything except anything about African art or African American art, but I traveled and took care of that part myself, she explained. Her travel to Europe and Africa throughout the 60s and especially in the 70s would be formative for her art making. I found my artistic identity and my personal vision in the 60s by looking at African masks; and my art form through the serial paintings (Migration of the Negro series) of Jacob Lawrence. The powerful geometry of African masks and sculpture that informed Modern art is what I like best about Picasso, Matisse and the other Modern European masters I was taught to copy. It is their exquisite compositions of shape, form, color and texture that make Picasso, Matisse and Jacob Lawrence's work so wonderful.

I got a fabulous education in art - wonderful teachers who taught me everything except anything about African art or African American art, but I traveled and took care of that part myself —Faith Ringgold

Through Ringgold’s work in schools and the art world, she was often in spaces that felt segregated to her, despite their claims to be liberal. Her works from the early 1060s, American People Series, reference that tension. She called their style of painting “super realism” in a reference to the stark appearance, flat planes of color and caricature-like features. I became fascinated with the ability of art to document the time, place, and cultural identity of the artist. How could I, as an African American woman artist, document what was happening around me? She asked.

As the 60s progressed Ringgold found it difficult to show her work in galleries. Even the all-male Black artists’ collective, Spiral, rejected her. She had her first gallery show outside of Harlem in 1967, at Spectrum Gallery, and she was their only Black artist. At the same time she started making the “black light” paintings which had a very specific tonal aesthetic, influenced by West African masks and textiles. This was mirrored by the current of Black Americans galvanizing around ideas of self-reliance and self-discovery, an impulse that began in the 1920s, exemplified by Alain Locke’s The New Negro anthology and the ensuing Civil Rights movements.

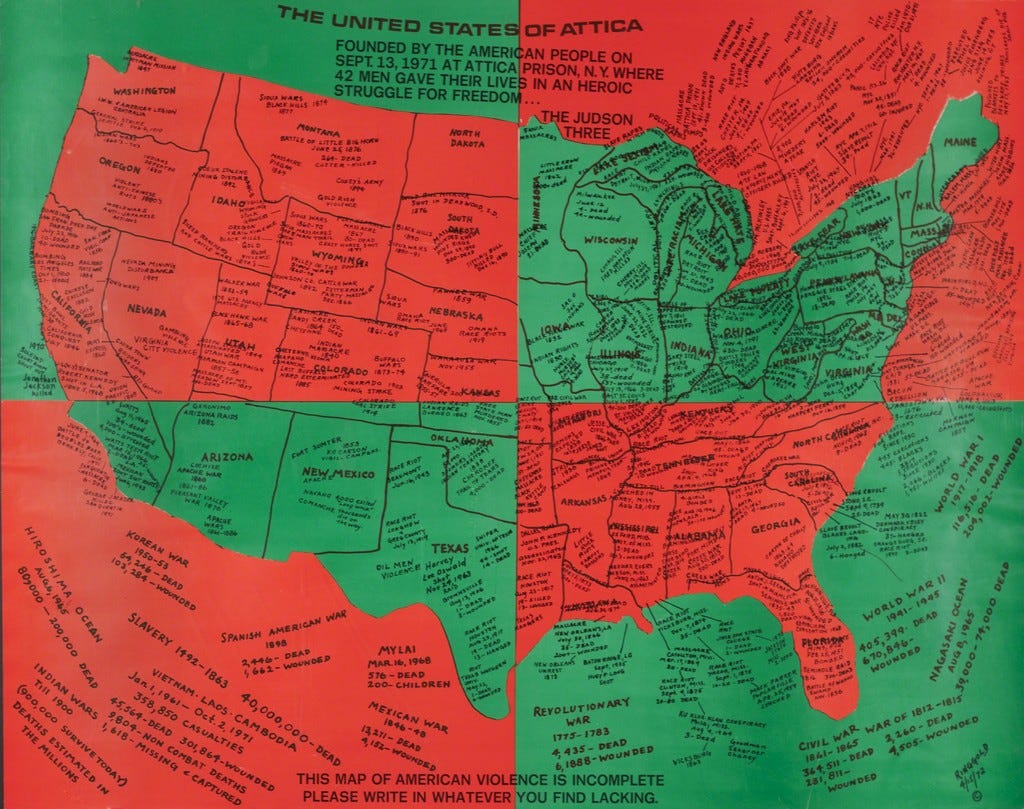

Another important facet of Ringgold’s work was even more explicitly political: she made beautiful, detailed posters for different political protest groups. Even though the Womens’ liberation movement was not at all intersectional, which she recognized at the time, she remained an active participant in civil rights discourse. In 1971, the prisoners of Attica Prison in New York protested against their inhumane living conditions and the national guard stormed the prison in response, killing 42 people who were begging for their human rights. Ringgold made a map of American violence in memory of this tragedy, and started supporting prison reforms, abolition, and art in prisons. She joined forces with her daughter, Michelle Wallace, and co-founded the Women Students and Artists for Black Liberation.

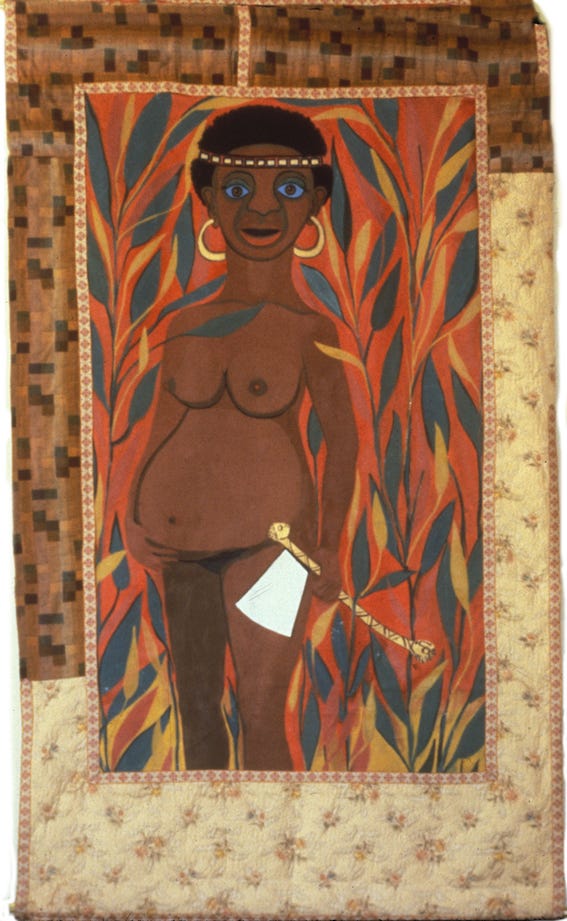

In 1972, Ringgold made a trip to Europe and spent time at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. A security guard who had lived in Harlem, New York, began talking to her about their shared neighborhood and pointed out that she might enjoy seeing the museum’s holdings of Tibetan paintings from the 15th and 14th centuries. These would encourage her to join forces with her mother, Willi, and collaborate on textile-based works (eventually these would become elaborate quilts). The first series that they made together was called the Slave Rape Series, of which there are twenty works total. Each depicts a nude Black figure, but is grounded in landscape. All the political people are buried in the ground which makes the landscape political, Ringgold said of these works. The titles are often instructive, emphasizing the role of the subject as a victim.

This was the beginning of her work in quilting, which she continues today. Ringgold has also published seventeen children’s books, has twenty-three honorary doctorates, and is currently working and living in New York City.

Faith Ringgold's jounrey through activcism and art, the Amsterdam Rijksmuseum, Tibetan art, late 60s - every aspects of your writing captures a bit of the revolutionary air, professor Sarah. One question by the way - it that a coincience that American people #8 reminds me of German Expressionism in the Weimar Republic where some artists were also focusing on critique of society alientation and decades of those in power? I don't know who this reminds me of, Otto Dix, Max Beckmann, Geroge Grosz?

"Even though the Womens’ liberation movement was not at all intersectional, which she recognized at the time, she remained an active participant in civil rights discourse." I'm circling back to this because it has irked me so very very much. Sorry, but it's flippant and wildly inaccurate. It's exactly what dominant media wanted and propagated and is so easily debunked, but a media course correction will never stick. Yes, white women didn't shed their racism as they struck a language for their own oppression. And of course there was Betty Friedan who is held up as a giant problem with her classism and heterosexism, and others who captured media attention and wanted it. But the Women's Movement was so much larger, more intersectional, and raw, and now misunderstood, and it happened at a time when so many movements reached for light and air. Read Susan Brownmiller's memoir In Our Time, A Memoir of a Revolution. I'm doing some research for a post at the moment and I came across this bio at Goodreads that should illuminate this era a bit: "Elly Bulkin, an activist since the 1970s, has worked in DARE (Dykes Against Racism Everywhere), Women Free Women in Prison, Women in Black (Boston), and other local political groups, and was a member of the National Feminist Task Force of New Jewish Agenda. She was a founding editor of two nationally distributed periodicals: Conditions, a lesbian-feminist literary magazine, and Bridges: A Journal for Jewish Feminists and Our Friends. She is co-author, with Minnie Bruce Pratt and Barbara Smith, of Yours in Struggle: Three Feminist Perspectives on Anti-Semitism and Racism (1984)."