In the early 2000s I was too young and broke to even consider taking time off of work for vacation. I did not leave the city even for long summer weekends, when the entire place empties out like a dump truck tipped over or an untied balloon slipped out of the hands of a kid—I don’t think I could have paid for a hotel—so the season stretched out, always, sort of infinitely, like I had all the days in the world to be outside. I was just young enough to be unaware of time passing—I did not understand the very idea that time would, no matter what, keep ticking. If I wasn’t at work I was reading mid century romance novels in my bikini in public parks, getting drunk in dive bars with my friends, or flipping through racks of vintage clothes on 9th street. I spent a lot of time wandering. Emile Zola might have called me a flaneur. The International Situationists might have said I liked to dérive. But I just liked to walk.

I never had an appetite, because I was always just broken up with. There was always a boy I liked, and he was always just rejecting me, and it was always making me need to walk and drink, which eating didn’t factor into, so my jean shorts would have to get rolled over on my waist and yanked up every few blocks. I discovered lots of corners of New York City like this, walking in a haze—not a haze because the city was humid but because my brain and my vision was clouded—distracting myself from perpetual heartbreak by bumping into friends and looking at strange buildings and wondering what happened inside of them. That’s how I first saw Westbeth: bony and too numb to be hungry, drunk, walking with my best friend up the west side, peering into wide industrial entrances and old tenement windows and hoping one of them would, eventually, be another bar.

The plaque on Westbeth’s facade tells you who’s lived there. Diane Arbus was the name that impressed me the most, and that’s what made me go inside the courtyard. It’s a strange place and though it was a science lab in the 1860s, Richard Meier redid it in the 1960s and added balconies facing the interior lot, so the residents—artists apartments and studios—could all see each other. Westbeth sounded witchy to me, Diane Arbus had always seemed like a witch, too; so I wanted to know what else happened at Westbeth. The place seemed to have an energy and stillness that was separate from the rest of New York.

Lots of artists had lived there (some still do). Merce Cunningham, Hans Hacke, Robert De Niro. Today we are going to talk about one of them named Howardena Pindell, who also happens to be one of the only Black women considered a part of the Pattern and Decoration movement, invited to their meetings and included in their shows. Though P and D painters advocated for the elimination of hierarchies that kept traditionally feminine and “global” crafting techniques out of high art, they did not go out of their way to include artists with diverse identities.

Born in 1943 in Philadelphia, Pindell learned how to draw figuratively in weekend classes at local universities thanks to supportive and liberal parents—her mother was a public school teacher and her father a public school principal and court administrator who had started a black teachers union and worked on cases with Thurgood Marshall. Pindell knew she wanted to pursue art as a career from a young age, despite some wildly racist encounters with white teachers and the parents of her white friends throughout her childhood (many of these are detailed in a video work she made in 1980, Free White and 21). She did her undergraduate studies at Boston University and then graduated with an MFA from Yale in 1967, soon moving to New York City and taking a job as an exhibitions assistant at MoMA. “There was very little employment for either black or white women artists,” Pindell would later explain. “I didn't try to get a job there. It was one of these flukes where I was wandering around trying to get employment. I had to go to the bathroom, so I had my membership at the Modern…Then I walked by the business side entrance, and I thought, "Well, why don't I go in and see if there are any jobs?" And I think it's because I had a real resume and also amazingly good luck.” She would become the first Black woman curator at the museum.

In 1970, when Westbeth was transformed from a science research center into subsidized artist housing and studios, Pindell applied and was one of the first artists to move in. She was making figurative work, but by the early 70s was diving into abstraction. One inspiration for this was the memory of a time her parents had taken her to the south to visit her mother’s family. Stopping at a root beer stand in northern Kentucky with her father, she was shocked that her root beer cup had a red circle on the bottom to indicate that it was to be used for Black customers. She credits this experience with the beginning of her fascination with circles: “There was a woman in Yale Graduate School, Nancy Murata, and she started playing with circles. And it was like a light came on, and I said, "Hm, I want to"—because I was figurative—"I want to try playing with the circles."” There was also the fact that by the time she got home from work it was so dark out that she found painting figuratively a challenge.

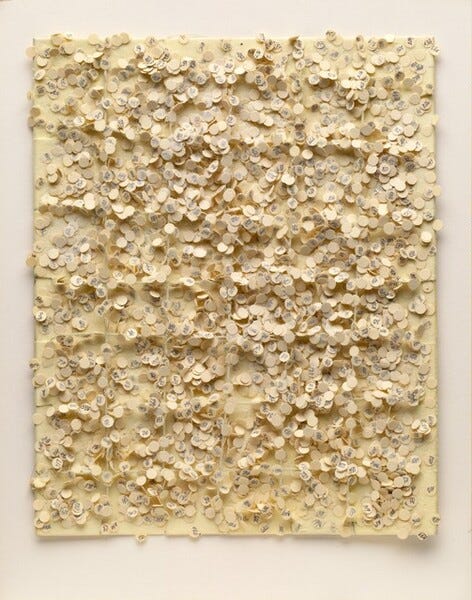

Pindell started using a standard office hole punch to create templates through which she would then spray paint, again and again in layers, onto a canvas hanging on a wall or placed on a table. This innovation yielded soft, undulating, beautiful works like Untitled, 1970. Soon, she began to use the punched out circles created by the making of the templates themselves, piling the dots onto the surface of canvases, sometimes numbering them. She often intertwined unconventional, traditionally gendered materials, like talcum powder, glitter, thread, and sequins into the surface of her works—perhaps inspired by the use of cowerie shells, hair and fabric that she observed in different African art practices during July and August 1973, when she took a months-long trip to Nigeria, Kenya, Ghana, the Ivory Coast, Uganda, Mali and Senegal (she spent this time visiting artists’ studios, printmaking workshops, universities, libraries, galleries and museums).

In 1972, Pindell won a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, which along with prestige brought her much needed funding (MoMA didn’t pay great and art supplies were expensive). In the same year she was invited to join a group of 20-some women artists who wanted to fund a non profit, artist directed and maintained art gallery for showing women’s art. She suggested calling it the Eyre Gallery, after Jane Eyre, but the group settled on A.I.R. Gallery, a phonetic play on Pindell’s suggestion that stood for Artists in Residence, Inc. Pindell would eventually leave this organization in 1975, faced with a specific kind of White Feminism that included a fellow member telling her, often, that Pindell “didn’t know she was Black.” This speaks to a conundrum she often mentions—feeling not quite at home among other Black artists, and not at home among white artists, either. She was a victim of racism among her white counterparts, but Black artists and groups did not like that her art played with tropes of minimalism, a style they saw as closely linked to white male hegemony, and they also saw her as a traitor to their causes as she worked at MoMA but didn’t have the power to acquire their work for the museum or put them into shows.

In 1979, a watershed moment occurred for Pindell: she was in a severe car accident and while her body’s fairly critical injuries recovered in a space of a few weeks, her brain injuries and memory loss sustained for months more, causing her to make a shift in how she approached the political within her art. She decided to start making work that was more personal in order to see if she could regain some of her memory loss by piecing her past together visually.

In Autobiography: Oval Memory #1, 1980-81, Pindell collages postcards and photographs from her travels onto paper, adorning the surface with acrylic paint. What began as an attempt to aid her memory recovery came to include making work that encompassed personal spiritual views, what she learned about spirituality and the treatment of women on her extensive travels through Africa, Japan, India and Europe; as well as her family’s multiculturalism and the racist and sexist abuse she’d received in her life. Other works in the Autobiography series included tracings of Pindell’s own body, references to AIDS, war, homelessness, climate change, genocide, and water as a metaphor for the Middle Passage and the tragic loss of Black life.

Pindell lives and works in New York City. She is currently a Distinguished Professor of art at Stony Brook University.

what a beautiful piece. love your own artistic history juxtaposed with others!

Love the combo of art and NYC walking tour. You might like to check out Dottie Attie. Another AIR founder. Art in America did a long cover article on her in 1994… She takes on misogyny in art history like none other