Her work was meant to question those norms and definitions written by men.

Though Yayoi Kusama’s story remains one of the most operatic, tales of infidelity and female suffering were not her sole burden to bear. Louise Bourgeois, for example, who was born in France in 1911, was also traumatized by a forced complicitness in her father’s affairs, which began when her mother was sick with influenza in the 1920s. Her parents owned a gallery that bought and restored antique tapestries, and Bourgeois spent her childhood doing her homework there. She continued working in the shop as she got older. So when her dad started sleeping with Sadie, Louise’s English tutor, and began bringing mistresses home, it was hard for her to avoid. I mean, it’s not like he had sex with them on the dining room table, but he would bring ladies around and be romantic towards them in front of his kids, while behind closed doors he was telling his wife he loved her. As an adult, Louise commented on her nascent understanding of the double standards related to gender and sexuality, and on the trauma of being a young girl exposed to the adult phenomenon of hidden emotions and suppressed hurt and sadness. Her father was the wolf, and she was the rational hare, forgiving and accepting him as he was, she explained.

While Bourgeois was in college in France, in 1932, her mom suddenly died, and it spurred her to abandon what she’d been studying and to pursue an education in art. Her mother had always encouraged her to draw and to sew, and she felt her mother’s death gave her permission to pursue what made her happy. To pay for her classes Louis worked as a docent at the Louvre, spending much of her time inundating herself with the art history in its walls. She opened her own art gallery adjacent to her parents’ tapestry shop, met a visiting American professor, and moved to the US with him, where she’d spend the rest of her life making a wide variety of artwork about the female experience.

Another fun thing about her is that once she was in New York, she made a practice of hosting salons in her home in Chelsea. She taught at both Cooper Union and the New School, and as such came into contact with a lot of young people. If any of them looked her up in the phone book and wanted a chat or a visit, she’d invite them to one of her salons, where they could come over for tea and meet her and the various members of the intellectual community in her circle. Bourgeois died in 2010, and her foundation has now turned her home and studio into a museum you can visit.

But about the art.

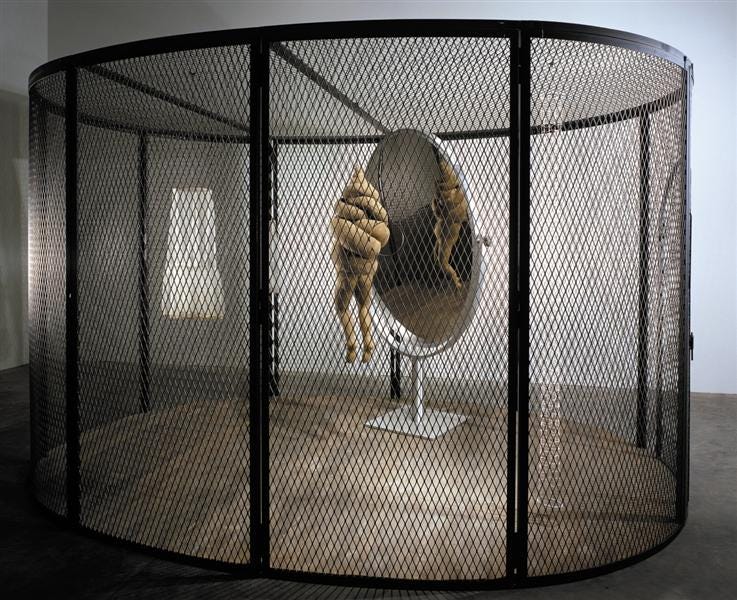

So much of Louise Bourgeois’ work explores the relationship women have to the home—to the domestic environment, to their own bodies, and to family. Because of this, a lot of her work includes textiles and embroidery—traditionally women's work, but also, in her own life, the profession of her family. She made paintings, such as the early Femme Maison, seen below, where she depicts the female body merging with the home, her sex organs drawn as clearly as the windows that replace her eyes. Bourgeois’ work progressed to stand alone sculptures, vitrines, and from 1989 on, some sixty large-scale Cells, assemblages of her own made sculptural works, with objects from real life, all contained within metal or wooden armatures. In some works, she even used her dead mother’s dresses and clothing, which of course carried strong personal and emotional charges for her. Many of these room-like installations include soft forms that she built to look like the body or anthropomorphized shapes meant to hint at the human experience.

In Cell XXVI, 2003, there is a hanging textile balanced by a voluptuous human-ish form displayed in front of a large mirror. The viewer is prompted to peer inward at the symbolic objects, and to Bourgeois, the assemblage represented a psychological state of distress. “Each Cell deals with a fear. Each Cell deals with the pleasure of the voyeur, the thrill of looking,” she said. She described herself as a “prisoner of her own emotions,” who could only be liberated by telling her own story. She considered her Cell works to be autobiographical and to challenge the concepts surrounding femininity such as patriarchal standards of beauty and the act of being looked at.

Being a mother wasn’t just defined by a virginal woman who was patient, reasonable, indispensable, neat and useful, all things a spider is, too, but it can also be grotesque and scary, menacing and monumental.

My favorite series by Bourgeois is a group of menacing steel sculptures meant to look like spiders. Some of these works are huge: one, over thirty feet tall and weighing almost 10,000 pounds, is called Maman– or Mother. She made these works at the end of her career, throughout her 80s. This one has no eyes. Nothing about it is friendly. From below you see its egg sack, its ribs, the part that spins its web. It is grotesque and scary, and how it could be maternal is incongruous. But that was her whole point—her work was meant to question those norms and definitions written by men. Being a mother wasn’t just defined by a virginal woman who was patient, reasonable, indispensable, neat and useful, all things a spider is, too, but it can also be grotesque and scary, menacing and monumental. There is a dark underbelly to womanhood, motherhood, and femininity—the pernicious and arbitrary standards and rules governing the acceptable ways to be each, for example, which have been made up by a patriarchy without women’s emotional and physical needs at its center—and only by representing that does one represent the full breadth of a woman’s experience.

another fab read. learning so much

I love you Sarah!