I became an artist when I figured out I could use the resources that I already possessed, my female perspective and my woman’s body. For me it was a therapy, it helped me become my own person, but at the same time it spoke to the condition of women in general.

—Martha Wilson

Despite a late bedtime and a lot of tossing and turning, I was up early the morning after the election, before anyone in my house, actually, which never happens. But I was already awake and moving when I saw the NYTimes alert pop up around 5am. I’d expected it, of course, and I already felt proactively weary. We’ve ridden this rollercoaster before, and I absolutely hate roller coasters.

I got showered, I got dressed. By 7am I’d gotten an email from the producer of my audio book recording sessions, the first of which was to start later that day. She’s an American woman who is based in Paris and does most of her recordings by zoom, from the living room of her apartment on the Canal Saint Martin (she’s clearly a genius). We’ve had a few more hours to process this than you have, and you’re probably just getting up. Let me know if you need some extra time today.

Into the studio I went. Luckily, the studio had a dog.

It also had lots of people to tell me what to do: a necessity, because I’d never recorded an audio book before, and I’d only listened to ones voiced by famous actors—you know, people who showed up to the recording studio equipped with a skill set. My advantage, if I had one, was that I knew how all the characters sounded as real life people, and also that I’d been thinking of every word of this book for over two years, testing out how it sounds in my head. So I sat there, starting just after the election results came in, for hours straight and days at a time, and read about how so many of the men I’ve come across in my life have harmed me, under the pall of widespread harm inflicted by the ultimate bad guy, the orange rapist in chief. It was strange. I was glad to be working. It felt right to be telling a story, especially one about the condition of being a woman. I didn’t laugh much because I’m sick of all my jokes, but I cried a lot, and we decided to keep that in the recording. The audio book will drop January 14th, the same day as my book (you can preorder both, and visit me on my book tour).

I’ve written about thirty of these Substacks. We started with women who would never have even heard the word feminist, because it didn’t exist yet, and we’ve made our way to the mid 1970s, when Richard Nixon was president. Some of the most avant-garde feminists made art in those years, and that’s how we’re going to move through this regime, too—radically. Still creating, still finding each other, still telling our stories, still speaking to the rage and resentment and resistance in women.

And that brings me to Martha Wilson.

Born in Philadelphia in 1947, Martha attended Quaker schools before studying English literature in college, leaving the USA for grad school as a sort of protest of the war in Vietnam. At Dalhousie University in Halifax, she’d wanted to write her thesis about Henry James, but her advisor accused her approach of being too visual. The interest level in her work was not high, which she saw as being related very much to her gender; “women don’t make it in the art world,” her mentor had told her. At this time, the neighboring Nova Scotia College of Art and Design was an incubator for conceptual art, and Martha walked over to apply for a job. She dropped out of Dalhousie and had a stint teaching English at NSCAD, though again she felt marginalized by the older, male professors.

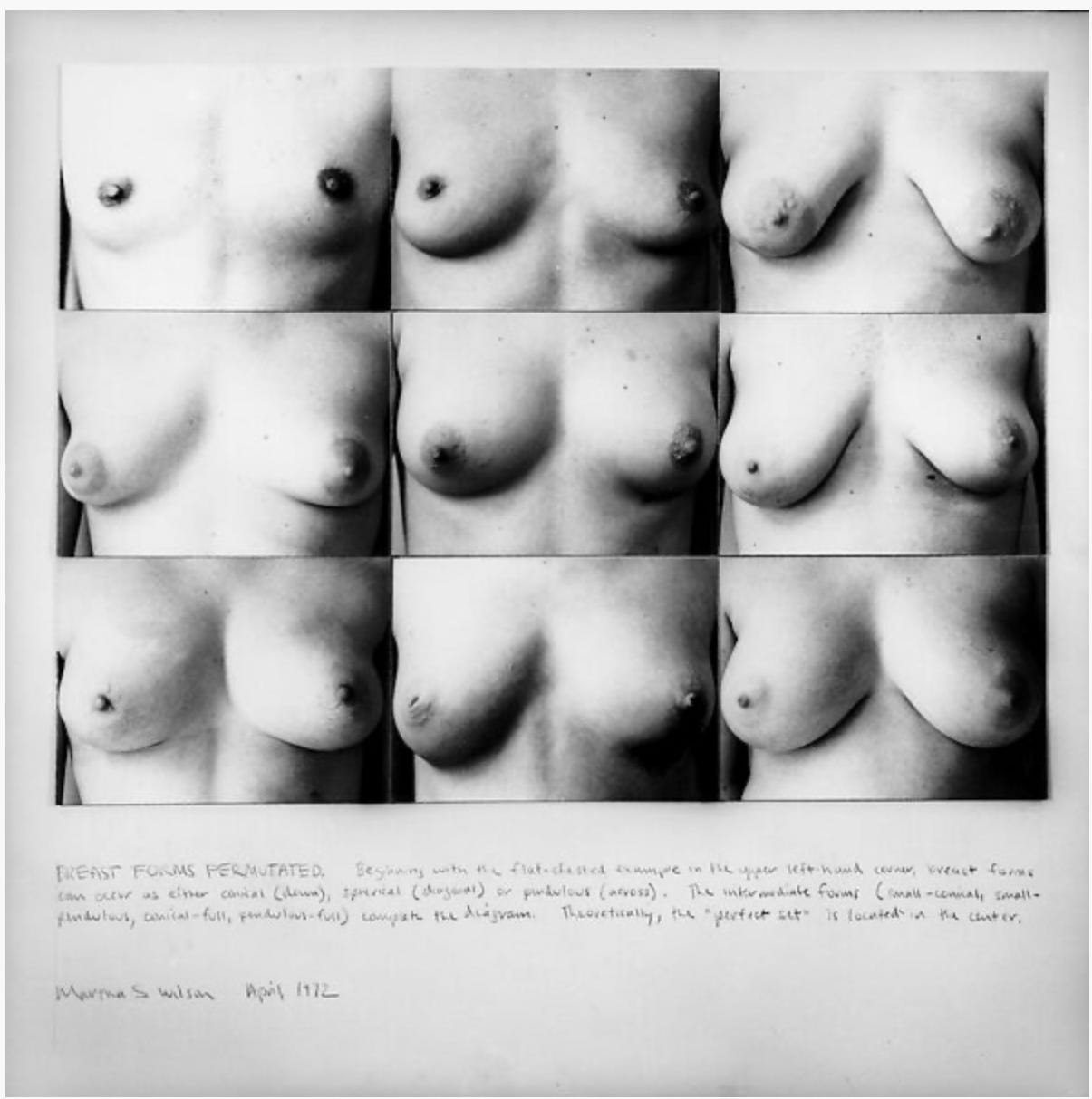

What came out of her time in the cold was multifold: she encountered the pioneering performance art of Vito Acconci, who made work like Trademark, 1970, where he sat nude in an art gallery and bit himself, a play on the role of an artist as one who makes marks. She became well versed in minimalism and conceptualism, and made her own versions of the minimalist grid but with gendered and fetishized body parts, like boobs, to point out how those art movements had traditionally lacked humanity and femininity—how they were a product of, and contributed to, the type of thinking that policed the female body.

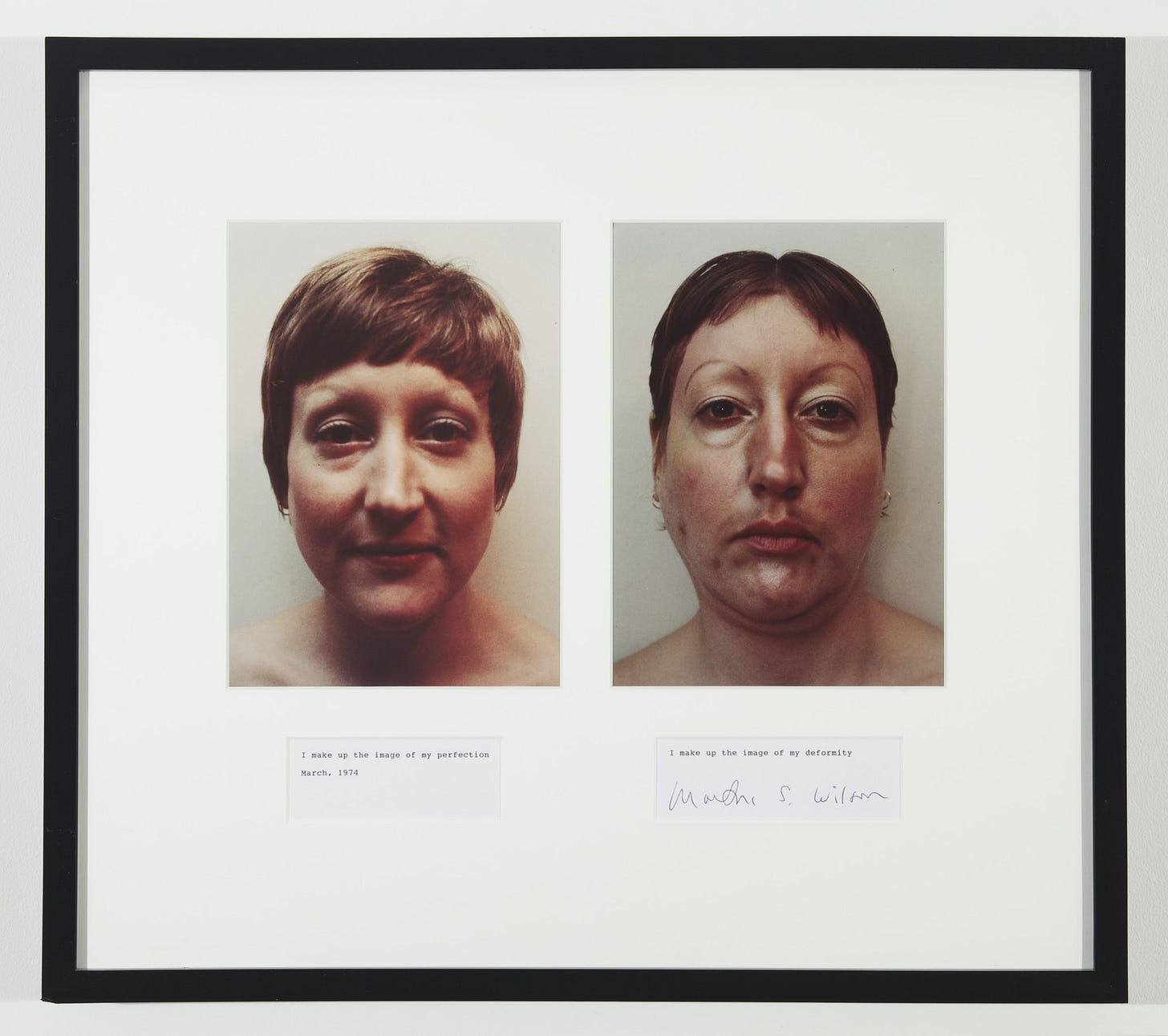

She also produced a groundbreaking body of photographic work, A Portfolio of Models, where, in her own words, she herself acted as “the models society holds out to me: Goddess, Housewife, Working Girl, Professional, Earth-Mother, Lesbian.” She photographed her own body and face in all sorts of drag: different genders, different ages—even as an old woman trying to look like a young woman. There was even a work called Suicide—a representation of a fake suicide, using ketchup as blood—which she called “an outlet through our art to get stuff out of our bodies and our souls.” She had, after all, been sexually abused by her father from the age of seven.

Though Martha was removed, in Halifax, from any feminist community, her work demonstrates the hallmark takeaways of feminist art: it tries to challenge the imposed roles on women as decided by male-dominated culture, by investigating identity and objectification—here, self-objectification. Luckily, our old friend, the brilliant cultural critic Lucy Lippard, went to Halifax in 1973 to check out the art scene, met Martha, and taught her the word feminist, which she’d never heard.

“Lucy changed my life,” Martha said. “… I had created a book with images and text of my different works. She looked at everything and told me, “Yes, you are an artist. There are other women around North America and Europe who are doing this kind of identity feminist work. I will put you in a show.” Lippard did, indeed, put her in a show at A.I.R. Gallery (which I write about here), and also introduced Martha to a curator named Jacki Apple.

Martha moved to New York City in 1974 and within a few years, together with Jacki Apple, opened her loft as Franklin Furnice, a nonprofit archive and exhibition space, with the idea that she could support performance and installation artists, as well as art publications that existed outside of the standard institutional confines. In her words, the space was an investigation of a new art medium: “time,” and therefore she wanted its focus to be as a library of radical artists’ books and notes. She would, eventually, sell the collection of written material and ephemera to the Museum of Modern Art, for $350,000 (this was, she noted, about what it cost to preserve and catalogue all that stuff), and in the late 90s she sold the loft itself for another $500,000, which she put towards making the archive an online repository, and supporting performance art projects.

She also made—and still makes—performance art herself, finding it to be a medium that has an important social lens. “It tells the story of AIDS, feminism, and Government financing,” she told the New York Times. Her work ranges from impersonations of Right Wing First Ladies and political figures to founding a feminist punk band made up of women who couldn’t play any instruments, called Disband.

Martha lives and works in New York City. Her most recent museum exhibitions include Invisible, Works on Aging 1972-2023, in 2023 at Frac Sud in Marseille, and in 2021, a show at the Pompidou Centre, Paris, called Martha Wilson in Halifax 1972-1974.

Wonderful read. Keep them coming