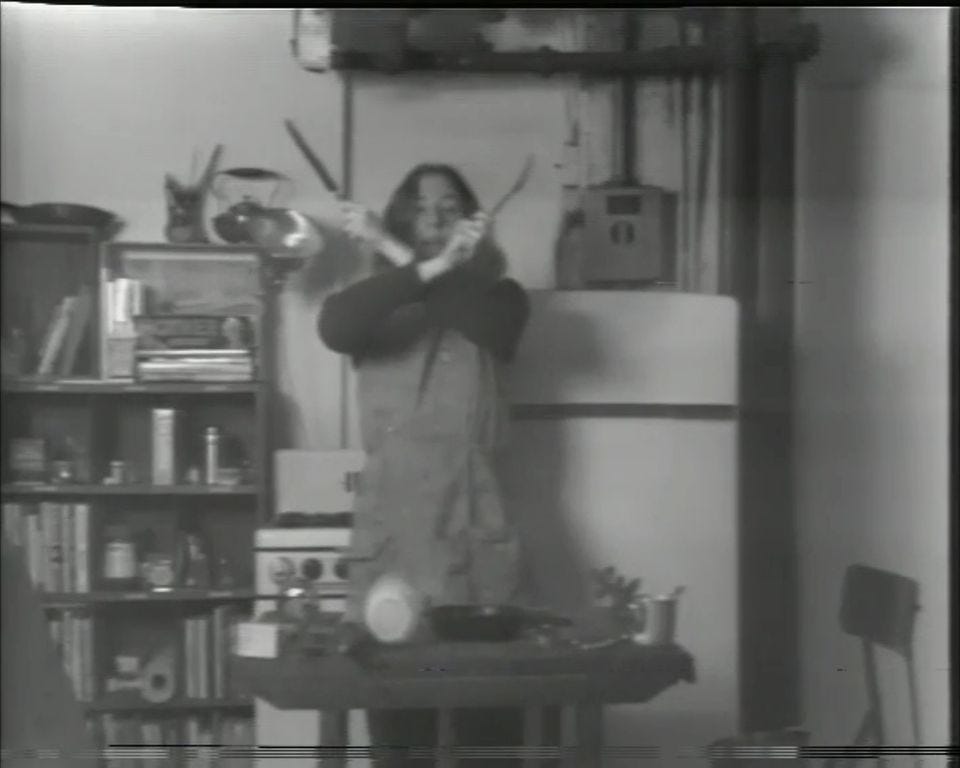

As the woman speaks, she names her own oppression—Martha Rosler

My first winter in New York, twenty-some years ago, we had so many blizzards that by February, the plows had piled months of snow and ice and trash onto the sidewalks, creating shoulder-height burrows you had to walk between to get anywhere. Or at least that’s how I remember it: a dusky, freezing city of snow mazes, all of which led to me being alone and lonely—I’d moved from Indiana without a single friend or contact—and a dark, sunless, winter matched my general late-teenage vibe. Winters are different now and blizzards seem to be merely a threat that rarely comes to fruition. In any case, I was able to get on a plane in the middle of the one that struck this past Tuesday and fly down to the Caribbean, where I’m spending a week off of school with some family, including my parents.

How long into a reunion with your mother does it take before you revert to your most hormonal, teenage self? How long before you start slamming doors and getting annoyed about…seemingly nothing? I’d say my average is approximately two days until I swing back into the truest version of me, which is, unfortunately, an annoying little bitch. I still have a few precious hours of being normal, and it’s got me reflecting on my childhood in a rational way, and something I think about a lot is how often my mom made dinner for our family, something I sure as hell never do. She—and I’m not hyperbolizing, though I am prone to that—cooked for us every single night. A real dinner, with a protein and a side and usually a type of potato, because Indiana, and always a big salad. My dad would sit at one table head with his glass of wine, my mom would sit at the other with hers and between the two of them we got reminded, like we were at a strange tennis match of manners, to chew with our mouths closed and put our napkins in our laps. We went out to dinner only for special occasions, and ordered carry out only if we had a babysitter. I’d like to add to this that my mother had a full time job and three children, a dog or two at any given year, and a husband who, like most SWM over forty, needed her to personally help him look for things like his cell phone and socks before they could possibly be found.

So why the pathological, self-induced pressure to make dinner?

”It was the only thing I was sure I was doing right,” she told me when I asked her earlier today. It wasn’t that she thought her place was in the kitchen, like she might of had she been a product of the 50s instead of the 60s, it was that she felt the kitchen could be a way to connect to family life, to find personal fulfillment. Julia Child had debuted her show in 1962, and her fame exploded in the 70s and 80s. My mom, Martha, had watched that diligently and been inspired to find something to reclaim about domestic work: she could find joy in activities that had, at one point, been only methods of oppression. In fact, she would be so inspired by her time spent cooking that she’d go on to open a chain of restaurants in the late 80s, eventually building the largest female-owned restaurant group in America.

She wasn’t the only Martha who was interested in the liberating potential of kitchen work. There was Martha Stewart, of course, whose story we all know well. And before either of them there was Martha Rosler, born in 1943 in Brooklyn.

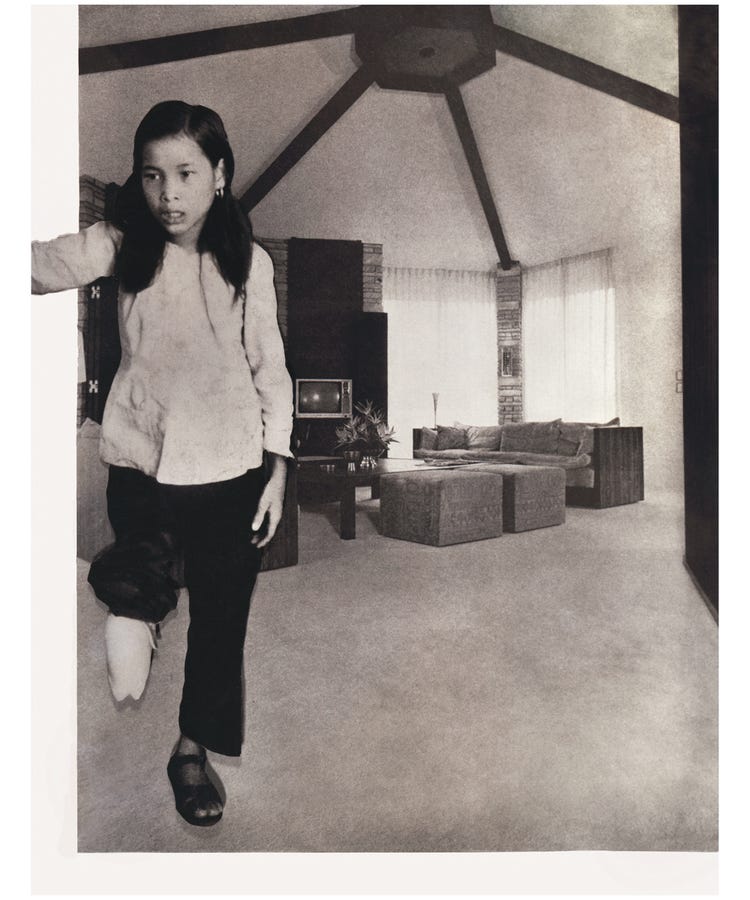

Rosler was politically charged from youth. As early as grade-school, she was writing about civil rights for her yeshiva’s newspaper, and she marched on city hall in high school, to the dismay of her parents, who held McCarthy-era worries about her proximity to Communism. Her family didn’t encourage her intellectually, but she went off to study at CUNY and graduated in 1965, married a poet, worked as an editor for encyclopedia while making art on the side, and then moved her young family (by then she had a son) to California in 1968, where she was introduced to—and smitten by—the burgeoning Womens’ movement. Already politically motivated, her introduction to the feminists of the California art scene radicalized her further. She was able to take her frustration and rage and channel it into early collages, particularly in the series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home (1967-1972), which called attention to the gaping chasm between the pain and suffering American government caused, and American culture’s sterilized focus on consumption. She used advertising and shelter images from House Beautiful magazine and spliced them with images of terror taken from Life Magazine of the Vietnam war—often referred to as a “living room war” because it was one of the first international battles understood by the general public through news consumed in their living rooms, on televisions. Rosler made the phrase more literal by photomontaging horrifying war graphics into images of well-appointed living rooms.

In the early 70s, after leaving her husband for a second and final time and returning to New York City, Rosler turned her focus to making video—a medium utilized by several feminist artists because it meant their work could be disseminated cheaply and easily. In Semiotics of the Kitchen, 1975, Rosler made a six minute film parody of a cooking show, a la Julia Child. It was a shitty, fuzzy, grainy, not-aesthetically pleasing video in which she went, alphabetically, down the list of kitchen appliances, demonstrating each one in an increasingly violent, resentful and unhinged way—pointedly emphasizing the oppressive ramifications of being confined to domestic tasks. “As the woman speaks, she names her own oppression,” described Rosler.

Rossler continued to make videos, photo collage and photographic installations throughout the 70s and 80s, about a myriad of political topics like homelessness, critiques of mass consumption, the beauty industry, and government disinformation. She’s had major museum shows at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the ICA Boston, MoMA, and the New Museum, and she continues to live and work in New York City today.

Sarah, I love your honesty and your writing. Thank you for sharing both.

Wow, Semiotics of the Kitchen was so ahead of its time! It's giving "Labour" by Paris Paloma. Thank you so much for sharing - this one really stuck with me.