Last week we took a look at the Italian Renaissance paintresse Artemisia Gentileschi, a proto feminist whose virtuoso painting allowed us a deeper dive into her personal life. Today we are going to skip forward about three hundred-ish years to post World War II America, to the glamorous 1960s—the Camelot era, a time when 90% of Americans had a TV set and everyone was wondering when we’d land on the moon. The long, arduous fight for desegregation in schools was beginning to make headway, and both John F. Kennedy and his successor, Lyndon Johnson, saw their terms consumed with civil rights issues, culminating with the passing of the Civil Rights Act in 1964.

Perhaps the chewing gum was a metaphor for the cultural worth of the American woman: chewed up and thrown out; used for labor during the wars and sent back to the kitchen as soon as peace returned, sexually exploited by men who were not, en masse, interested in women’s political equality.

In the 1950s, European cities like Paris and London that had been traditional hubs for culture-defining artists gave up their seats to the “New York School,” a loose group of mostly white male painters, poets, musicians, composers, and dancers who lived in New York City. After the horrors of the two world wars, it seemed almost disrespectful to continue making art the way it had always been made, about topics that had long been treated as “normal.” Nothing was normal anymore. Artists questioned their faith in God and religion and nationalism, and banal subjects like landscape or biblical allegories seemed too nostalgic for a recent past that had been consumed by abject violence and terror.

The New York School painters mostly championed what was called Abstract Expressionism, a painting style which had two subtypes—action painting and color field painting. Other art movements of the post war period included Pop Art, Minimalism, Conceptual Art, and Arte Povera. We’ll get back to all those later. What’s important for now is that you know that they were dominated by white men. The critics of major publications who codified artists as important were white men, and the heads of major museums who bought the work of artists deemed important were white men. Basically everyone who was “anyone” was a white man.

And then came Betty Friedan.

When The Feminine Mystique debuted on bookshelves in February, 1963, I don’t know if Friedan understood just how much her book was going to shake up America. I don’t know if she realized she’d written a huge bestseller, which would sell over two million copies. I don’t know if she intended to end up a leader of the Feminist movement, a founder of the National Organization of Women (1966), or an instigator for the Equal Pay Act of 1963. I do know that she was fed up.

Fed up because when she was offered a prestigious fellowship in psychology, she felt she had to turn it down so her boyfriend wouldn’t be intimidated by her success. Fed up because when she told the boss at her newspaper job in New York that she was pregnant, she got fired. Fed up because when she went back to her fifteen-year Smith College reunion, excited to catch up with her female peers, she found them dissatisfied, depressed, over-medicated, and miserable.

“The problem that has no name,” she wrote, “was the inability for women to feel fulfilled living up to their socially-prescribed gender role as mothers and housewives, with no freedom or ability to pursue their potential.” And with that definition, she launched the second wave of feminism (The first, in the early 20th century, had centered around political equality for white women; its aims were primarily to secure their right to vote). Early second-wave feminists of the 1960s, women who had just read Friedan, were shaping their worldview around the nascent ideas that a woman could be a valuable person without fulfilling the imposed role of housewife. While our current understanding has moved far beyond the notion that gender and sex can be reduced to such a strict binary, men on one side and women in the opposite corner, second-wave feminists believed that the equality of the sexes was essentialist, firmly rooted in the idea that women are inherently different from men, and are defined by those differences. And they posited that what is essentially female, while different from what is essentially male, is equally valuable and worth exploring. For second- wave feminist artists, the essential-ness of womanhood was what their art should be about. For some of them, this meant making art about pussies.

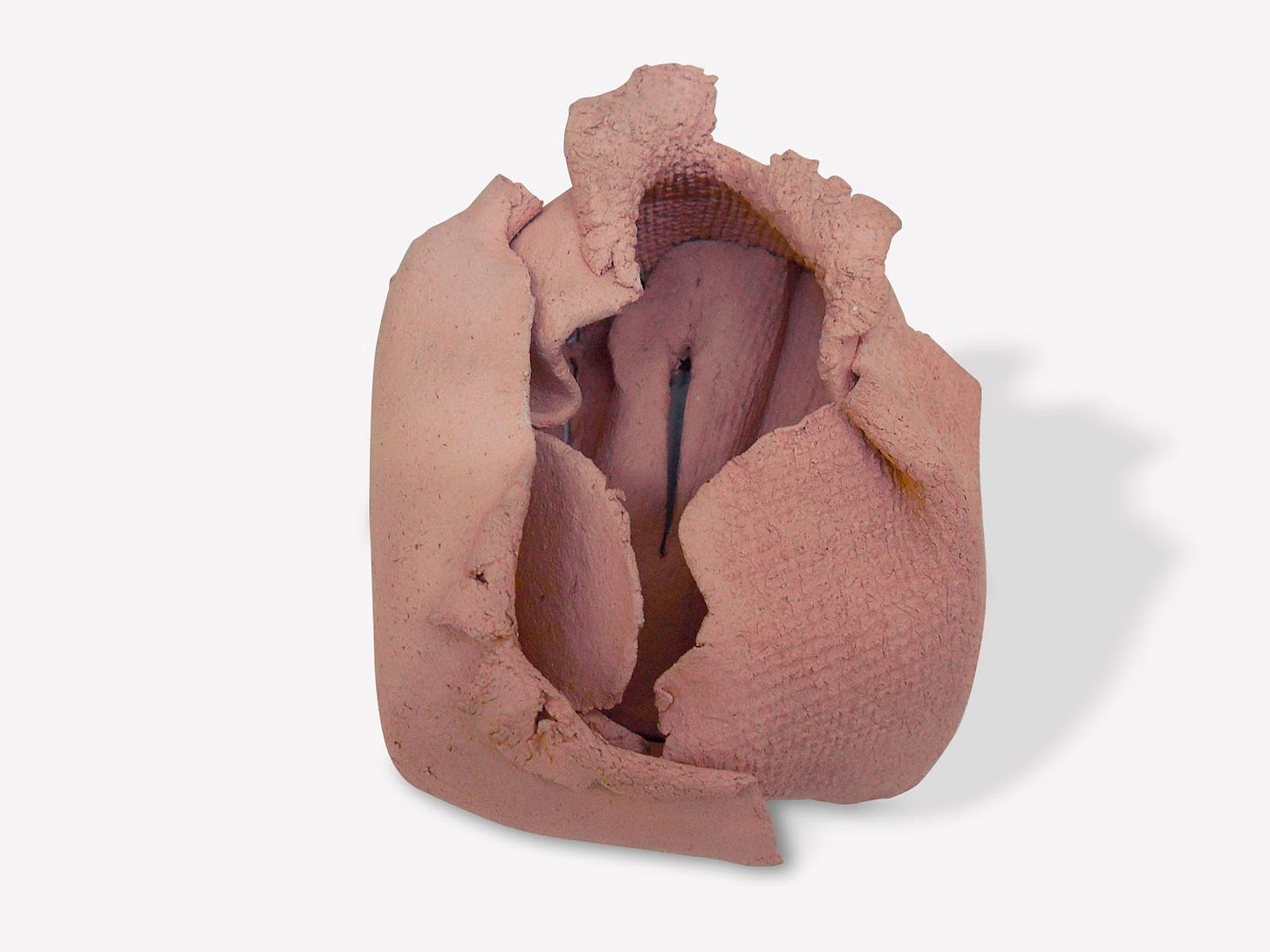

Hannah Wilke. Untitled, c. 1960s. Terracotta. 5 1/4 × 4 × 2 7/8 inches. Hannah Wilke Collection and Archive, Los Angeles.

Not pornographic pussies, not pussies meant for only being looked at, or pure enjoyment, or the function of fertility. But vulvas imbued with reclaimed political meaning, with pride and ownership. “Since 1960, I have been concerned with the creation of a formal imagery that is specifically female, a new language that fuses mind and body into erotic objects that are namable and at the same time quite abstract,” explained Hannah Wilke (b. 1940, NYC), one of the earliest artists to make political art using explicitly vulvic forms. Her first sculptures, terra cotta clay shaped into small, folded, clitoral shapes, repeated themselves throughout her career in a variety of media: chewing gum, laundry lint, erasers, and latex were used in free-standing sculptures, wall hangings, and on top of photographs, and the artist’s own body until her untimely death from lymphoma at the age of 53. Her own mother had died of the same disease in the eighties, a process which Hannah commemorated in photographs and paintings. “Baldness and emaciation from chemo became my mother’s Auschwitz,” she said.

When Wilke was dating the Pop Artist Claes Oldenburg, she went to see him in Los Angeles, and made a special pilgrimage to the important feminist artist Judy Chicago’s studio. After presenting her work to her fellow artist, Hannah was told, curtly, to “give up” making art. One of the great feminist art critics, Lucy Lippard, writes, in 1971, “The rare woman who has made it into the public eye tends to reject younger or lesser women artists for fear of competition, for fear of being forced into a ‘woman’s ghetto,’ and thereby having her work taken less seriously.” But many other dearly regarded artists and art historians criticized Wilke as well; Judith Barry and Sandy Flitterman argued that her work, “in assuming the conventions associated with a stripper…ends up reinforcing what it intends to subvert.” Hmm.

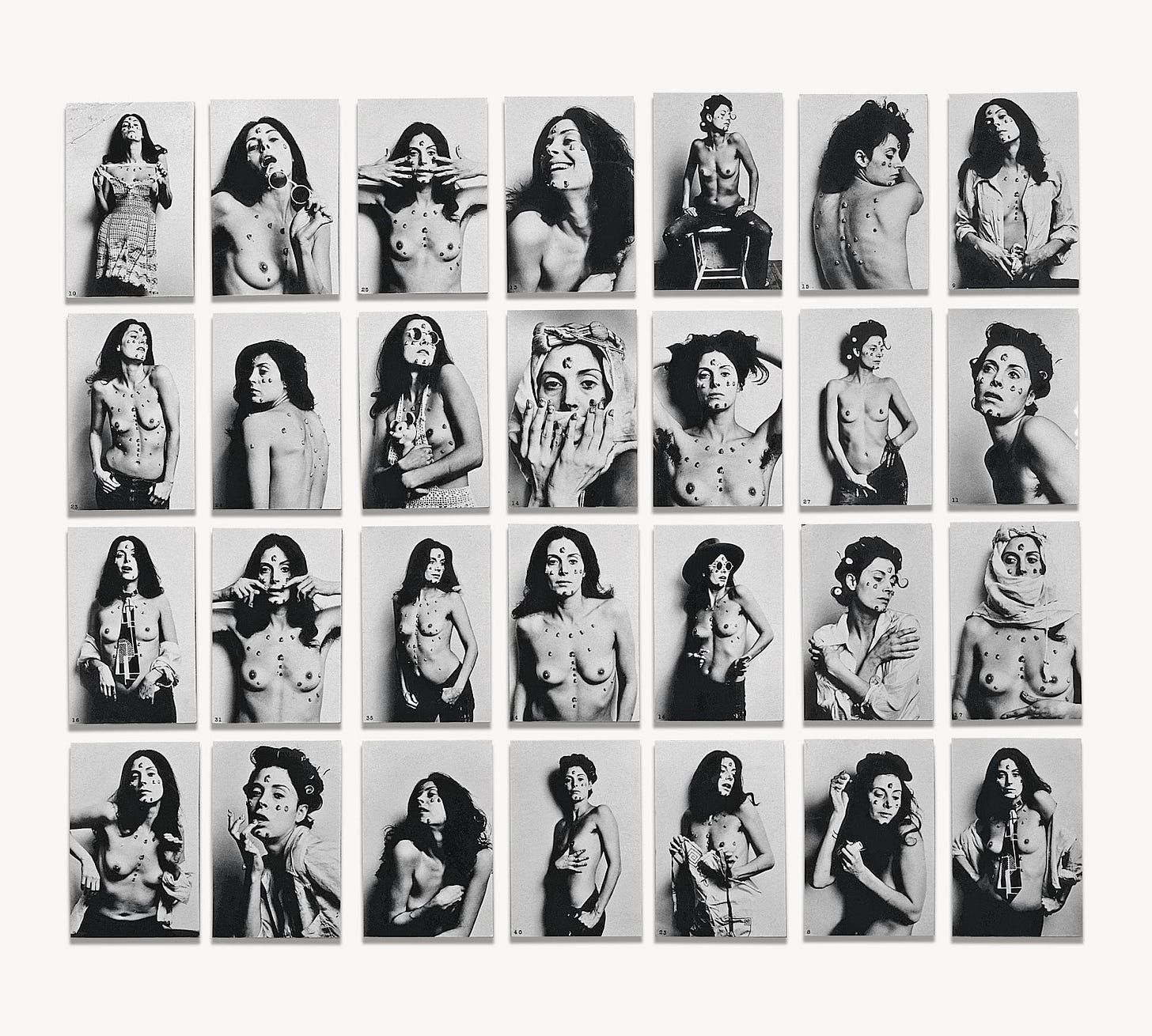

They were all probably really mad at Hannah about the works in S.O.S. (Starification Object Series), a group of self portrait photographs in which her seductive and nude form is covered—her body literally scarred—by vulvic sculptural shapes made of unconventional materials, which nodded to the historical lack of access to traditional art supplies and education that women had long faced. This gesture also placed Wilke in the trajectory of proto-feminist artists like Eva Hesse, a pioneer of soft, organic-formed, minimalist sculpture made from industrial ingredients like resin (we’ll get to her, too).

One work in this series formed small vulvas made from lint she collected while doing her boyfriend’s laundry; another used vaginal forms chewed from gum. In all of them she posed like a pinup girl, her sharp cheekbones and elegant profile on display. By using her own image, Wilke seemed to deconstruct female vanity and celebrate her sense of self. Perhaps the chewing gum was a metaphor for the cultural worth of the American woman: chewed up and thrown out; used for labor during the wars and sent back to the kitchen as soon as peace returned, sexually exploited by men who were not, en masse, interested in women's political equality. Hannah’s juxtaposition of glamorous poses with aggressively vaginal imagery satirized the gendered and stereotypical understanding of feminine beauty—women can exist, it seemed to say, but only the acceptable parts.

And so she was part of a burgeoning movement in the sixties of women operating outside of the New York School, outside of the other art movements that all the white guys held dear. And no offense to the white guys—many of them made sublime art during this time—but Hannah and her compatriots were making smart, valuable, meaningful and beautiful contributions to culture, too.

We’ll keep talking about Hannah and crew next week, when we look at more art made not only about vaginas, but with them…stay tuned. Study Hall is in session.

i need to learn more about Hannah Wilke!!

I spent almost 10 years in art school in the late 80’s-90’s and there were so few women mentioned in art history (just for example) I have often wondered if it’s worthwhile trying to get my money back from the institutions that withheld them from everyone. Sigh.