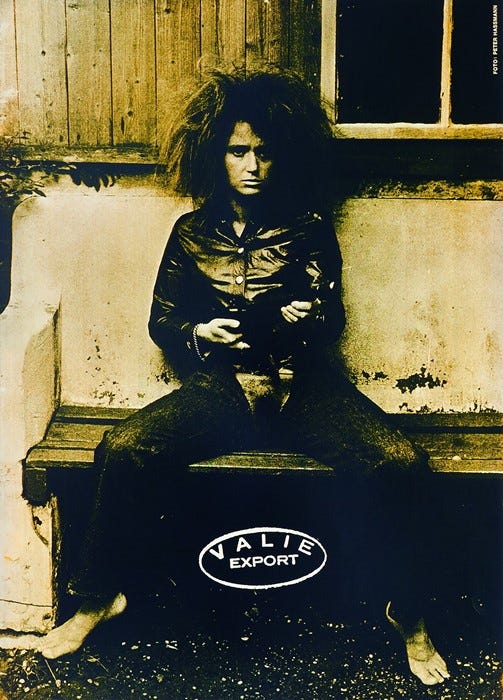

VALIE EXPORT

Celluloid you can burn but VALIE EXPORT you can’t

As long as the citizen remains satisfied with a reproduced copy of sexual freedom, the state will be spared a sexual revolution—VALIE EXPORT

Waltraud Lehner was born in 1940 in Linz, Austria, the third daughter of a single mother whose husband died fighting for the Nazis when Waltraud was an infant. This was a common story in postwar Austria—in any Nazi territory, really—where the generation that emerged from the 1940s would have to grapple with phenomena like the complacency, guilt and participation of their parents in the atrocities of war. This compelled a search for new ways of living, new philosophies on life, and new outlooks following the tragedy and destruction of an incredibly violent six years. A preoccupation with these topics became fodder for many art movements across Europe, as well as for political change—two examples include the founding of the Green Party and the sweeping European revolutions of 1968.

In the arts, a radical movement called Viennese actionism, characterized by purposefully shocking transgressiveness, a deep interest in violence, and the use of the artist’s own body in deranged and destructive ways, emerged in Vienna. The main proponents—names like Gunter Brus, Otto Mughal, Hermann Nitsch, and others—created actions, or intense public performances. For example, in the late 60s, Brus performed an action where he simultaneously masturbated, covered his body with his own shit, and sang the Austrian national anthem. A wild time! It’s important to mention that this resulted in his being wanted by the police and fleeing the state. A lot of these artists would end up being arrested and prosecuted, or would choose to go on the lam. Despite such down sides, the Viennese Actionists’ tactics appealed to Waltraud, who by 1967 had left her Catholic high school (it was, literally, in a convent), studied fine art (painting and sculpture) at university in Linz, married, had two kids, moved to Vienna to study design at the National Technical school, started making films, and changed her name to VALIE EXPORT (all caps), which was derived from the branding of an Austrian cigarette brand.

This was not a Warholian gesture, subtly inquiring about commercialism, this was—by virtue of her rejection of the last names of her father and ex-husband—a challenge to mass production and its connection to patriarchy’s power.

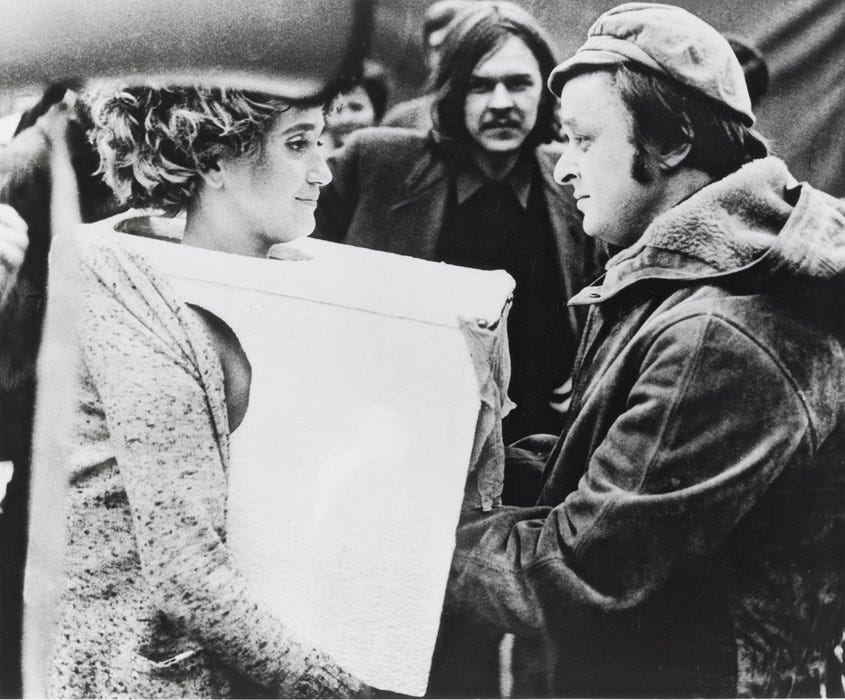

Moved to art-making by her “own clear sense that something else was really not right, that boys were allowed to do so much more than girls,” VALIE EXPORT considered her early works of the late 60s and start of the 1970s as chief examples of the expanded cinema movement, a phrase she coined to refer to performance artists and avant-garde filmmakers attempting to take film outside of the traditional theater environment, and to make it more provocative. As a young feminist, EXPORT imbued these aims with the goal of exploring how film, art and society were entrenched in patriarchy. In 1968’s Tap and Touch Cinema (Tapp and Tastinko), for example, she collaborated with the Viennese Actionist Peter Weibel, who called participants from a crowd using a megaphone while EXPORT wore a styrofoam box with a curtain covering the front, her naked breasts underneath. “The tactile reception stands against the deception of voyeurism,” she explained. Together they walked through crowded areas, inviting strangers to reach inside the box and feel her breasts, hoping to call attention to the ways that traditional cinema sexualized the passive female form. She did this, by the way, during a film festival, near the theaters where the official movies were being shown. “In that I, in the language of film, allowed my…chest, to be touched by everybody, I broke through the confines of socially legitimate social communication…the woman attempts through the free availability of her body to determine her identity independently: the first step from object to subject.” As part of her feminist aims, EXPORT wanted new views towards Womens’ sexuality. “As long as the citizen remains satisfied with a reproduced copy of sexual freedom,” she said, “the state will be spared a sexual revolution.”

A few months later, in 1969, came EXPORT’s Action Pants: Genital Panic, and this piece was also enacted in the public sphere, but this time in Munich inside the movie theatres. EXPORT had fashioned a special pair of Mustang jeans (her aktionhose) with the crotch removed, exposing her genitals entirely. She wore these while wandering movie theatre rows, facing the seated viewers so that her crotch was right at eye level. She also had a machine gun slung over one shoulder—a particularly antagonistic gesture meant to highlight her desire to confront, aggressively, how women are expected to be sexual. “I did not move in an erotic way. I walked down each row, the gun I carried pointed at the heads of the people in the row behind. Out of film context, it was a totally different way for them to connect with the particular erotic symbol.” I’ll say. These early Guerilla performances were considered some of the first feminist actions in Europe, laying the groundwork for what feminism and feminist art would look like there the next several decades.

Through the lens of feminism, EXPORT hoped to analyze more than just the role of women. In her Women’s Art: A Manifesto, from 1972, she advocated for women to “speak so that they can find themselves, this is what I ask for in order to achieve a self-defined image of ourselves and thus a different view of the social function of women.” But her art shows us that more than personal growth, she hoped feminism could be a path for examining all systems of power. Along with philosophers of the time—like Michel Foucault, who published Discipline and Punish, a study of penal systems, in 1975–EXPORT’s interest lay in exposing the power structures and political systems that had allowed for the destruction of the war that shaped her early life.

A favorite work that exemplifies this is another performance collaboration with Peter Weibel, where she led him around the busiest areas of Vienna on a leash, with him on all fours like a dog. “Here the convention of humanising animals in cartoons is turned around and transferred into reality: Man is animalised – the critique of society as a state of nature,” said Weibel. Portfolio of Doggedness, 1968, thus inverses several power dynamics, spelling out a metaphorical path for how her art could inspire change in the viewer’s worldview.

EXPORT has never achieved widespread recognition or celebration for her groundbreaking works, partially because of her own reluctance to participate in gallery and museum structures, but also because of the Austrian public’s revulsion towards her. In the 70s, the Austrian press even branded her a witch, and not in the good way. “Celluloid you can burn, but VALIE EXPORT, you can’t,” said one newspaper. Nevertheless she has persisted, and has gone on to make films, film installations, computer animations, photography and sculpture. She lives and works in Cologne, Germany, where she has a professorship.

Fascinating! Thank you for illuminating this side of art history for me. The courage this woman has is very inspiring and I'm glad to hear she's teaching the next generations.

What an amazing woman... thanks for this.