While a hundred years before, painters like Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot had depicted motherhood, it had been with idealized and beautiful images…

I managed to dull the memories of a lot of my last pregnancy, and one of the things I forgot in the process is that being with child is like having an extra full time job. It’s not just the regular trips to the obgyn and assorted other doctors to help manage the growing list of painful, uncomfortable and sometimes dangerous symptoms that require both treatment and monitoring, it’s also the constant emotional burden; the worrying about every little kick (or lack of kicking) which often results in calling the doctor in a panic; the wanting to soak up time with already existing children who have their own emotional needs surrounding an incoming sibling; the wild insomnia that the human body provides in order to get you used to a newborn’s sleeping patterns; the feeling—for me at least—that my brain suddenly has holes in it, has become a veritable Swiss cheese of gray matter that forgets important things and cries about stuff that isn’t sad and feels euphoric over random shit like tacos. I know it’s supposed to be the most beautiful or magical or special time in my life, but I mostly just feel like a walking hormonal experiment who can’t accomplish anything that doesn’t have to do with the immediate needs of pregnancy (I did order a bunch of baby crap last week, and I even took it out of the boxes, which was similar probably to what it’s like to climb Everest). This is why I have not managed to sit down and write a weekly Substack for three weeks. I have no better excuse than this: my life is overwhelmed, my brain is broken. My baby, I’m worried, is not a trauma-informed feminist with a deep love of art history and the bandwidth for weekly research and essay writing. But I will keep plugging along, and in these final weeks, please try to show me some grace if I dip in and out a bit…and please indulge me as I write about art that deals with the exact same stuff I’m dealing with.

This seems like a good time to talk about Mary Kelly, one of the few feminists of the 70s to make art explicitly about the maternal. “Traditionally, the ability to produce children and the emotional relationship that ensues have been held up as the reason for women’s lack of creativity,” wrote Laura Mulvey in a 1976 review of Kelly’s potent work about her pregnancy, Post-partum Document, 1973-79. This very notion makes me want to set the world on fire. What could be more creative than literal creation?!

Kelly was born in Iowa in 1941, but was raised in a Catholic, modest household outside of Minneapolis. She went to college in Minnesota, but then, through the Catholic Church, got a scholarship to study painting in Florence, Italy, where one of her tutors suggested her for a job teaching art lessons in Beirut, at what is now called the Lebanese American University. She stayed in Lebanon during the six-day war (1967), and was profoundly impacted by her new, up-close understanding of colonialism. In her french-educated circle in Beirut, she was introduced to revolutionary cultural theory by writers like Jean-Paul Sartre.

In 1968 she moved to London to attend graduate school at Saint Martins, embedding herself within the leftist movements there. She met many important leftist theorists in this milieu: Laura Mulvey, who would go on to write about her (and many other feminist artists and filmmakers), psychoanalyst Juliet Mitchell, and a fellow artist, Ray Barrie, who she began a relationship with and is still with today. Together they lived in a women's commune on Alderney Street. And it was in this commune, where domestic labor was entirely shared, that she found herself pregnant and gave birth to a little boy in 1973. She would go on to turn the first years of his life into one of the most groundbreaking artworks about the maternal experience ever made: Post-partum Document, 1973-1979.

The press around this work, first exhibited at the ICA London in 1976, was disparaging and explosive, deriding her work as “rubbish,” sort of proving her point—that art history truly did not care about this aspect of humanity.

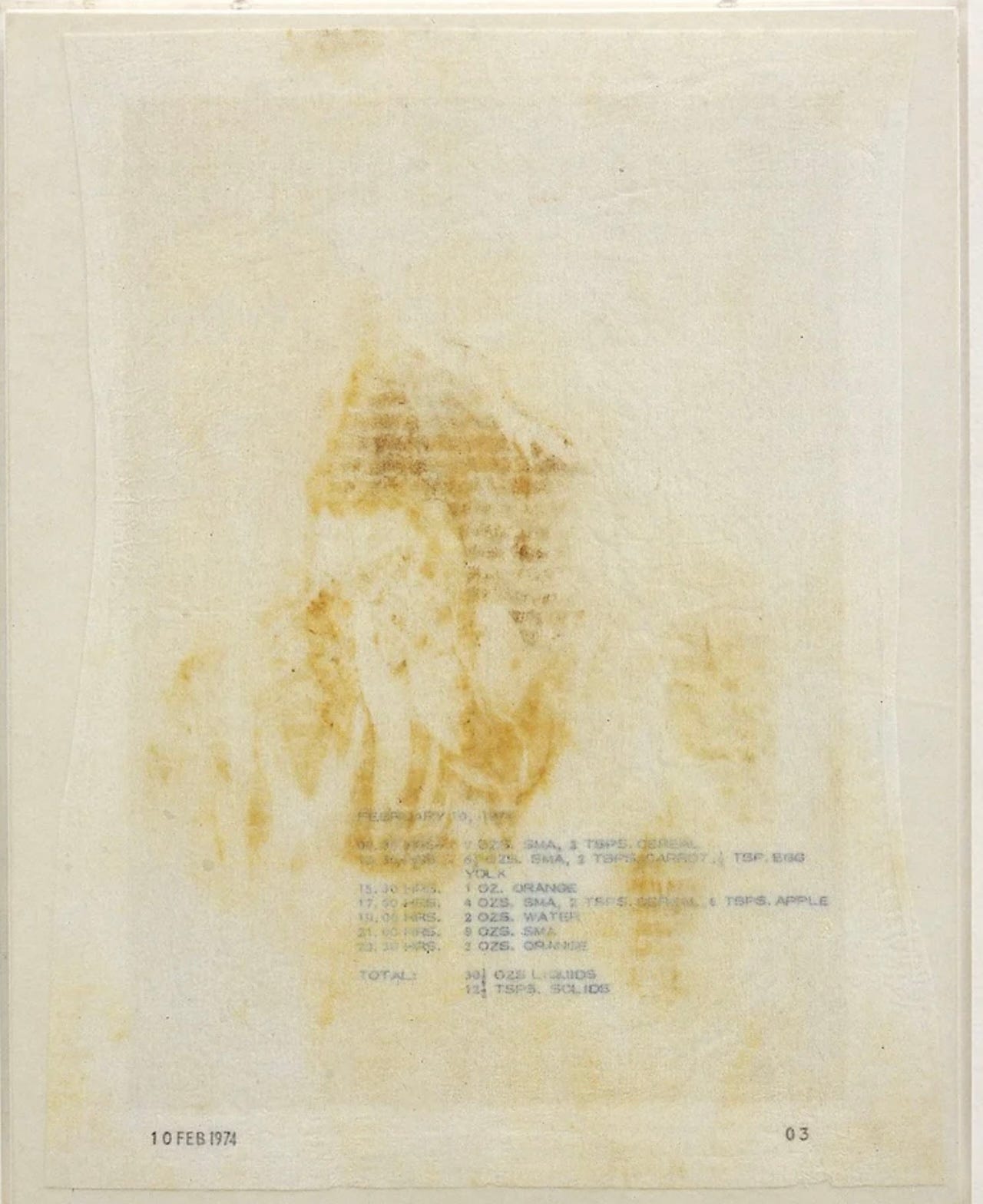

PPD began as an installation documenting the early stages of Kelly’s son’s life (confusingly, his first name is…Kelly). In six parts, the installation includes actual objects and records of his physical existence (scraps of his blankie, his clothes, his soiled diapers, his scribbled artworks; the feeding charts she used to organize her care of him, her notations measuring his breastfeeding and his shitting), as well as her own written documentation of the experience of mothering him, utilizing Freudian and Lacanian language to analyze her feelings towards mothering, which she described as “totally psychotic if you want to know the truth.” Preach. The installation starts with his infancy and ends with his learning of speech (she ended her project when he learned to write his own name around the age of six)—when she felt he really started to separate from her as an individual. Freud postulated that men feared castration—of different appendages, but particularly the penis. But for women, he thought that castration fears involved separation from their sons—not only in the worst case scenario of death, but in the standard ways a child would grow up and leave her. To distract from this, he wrote that women would fetishize their child’s output by saving what Kelly calls “mother’s memorabilia.”

“There was nothing in art that tried to understand or express this aspect of our lives: our relationships to our children. The earlier generation of women tried to pretend they were men,” Kelly explained. She, on the other hand, leaned into her personal story and emotions, using it to create vitrines and displays that looked like they were more suited to an archaeological or natural history museum.

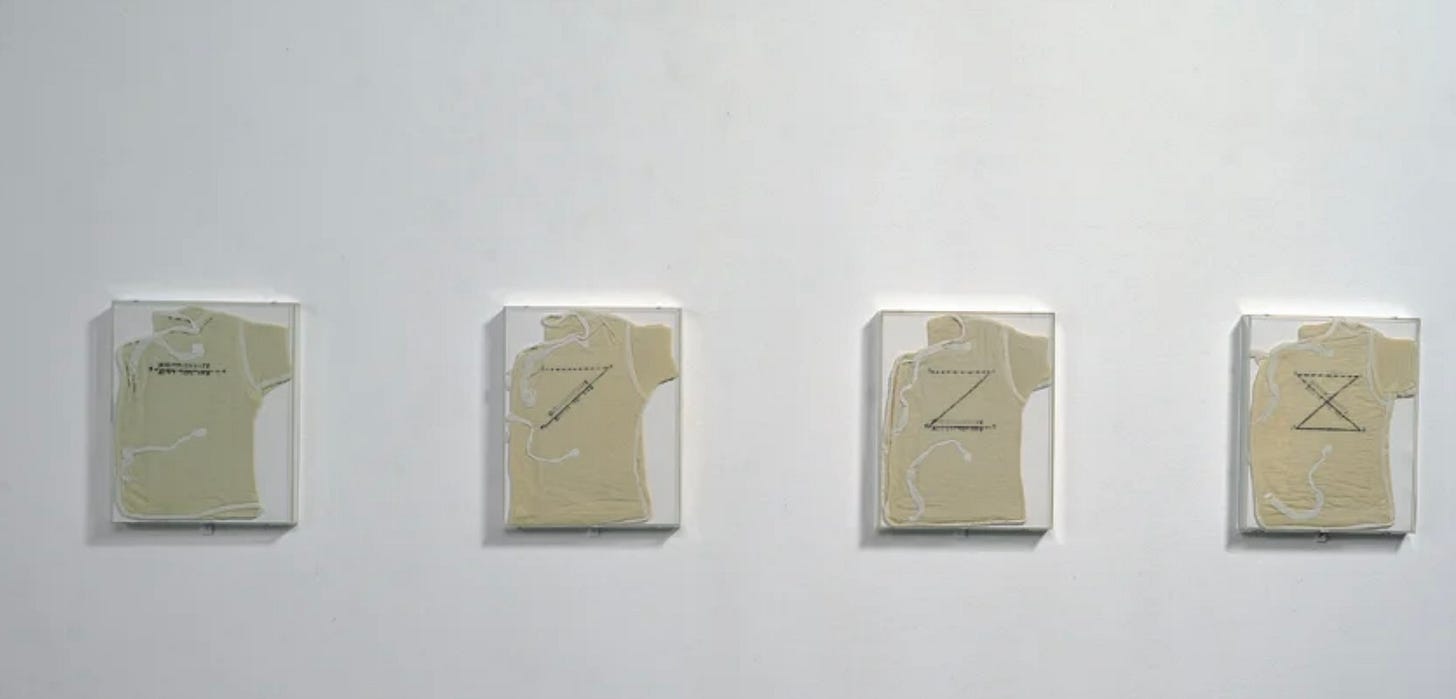

In Introduction, 1973, the first part of the PPD, Kelly drew Lacanian diagrams onto four wool outfits that her son had outgrown.

In Document 1: Analyzed Fecal Stains and Feeding Charts, 1974, she listed the foods he ate and included his resulting diapers. The press around this work, first exhibited at the ICA London in 1976, was disparaging and explosive, deriding her work as “rubbish,” sort of proving her point—that art history truly did not care about this aspect of humanity.

This idea that women’s experiences had been left out of consecrated art history narratives was a driving force behind feminist artists in the 60s and 70s, as you all well know. While a hundred years before, painters like Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot had depicted motherhood, it had been with idealized and beautiful images. Kelly utilized a very specific strategy in her fight, co-opting both the look and the language of masculine, psychoanalytic and philosophical discourse. Other conceptual artists of this era also relied heavily on text and critical theory; famously, Douglas Huebler, Lawrence Weiner, John Baldessari, Bruce Nauman—but they were all men. She borrowed their methodology to both parody the male understanding of motherhood and also to point out that maternal labor did not have to be based on a woman’s “maternal instincts,” the existence of which she thus called into question. If women were not necessarily inherently better suited to doing all the parenting, then perhaps the division of labor was not quite fair?

Kelly was, generally, interested in labor. She collaborated on a documentary called Nightcleaners, 1970-75, about women janitors who cleaned offices at night so that they could care for their children during the day. Along with Margaret Harrison and Kay Hunt, she created the Women and Work project, 1973-1975, which further analyzed psychoanalytic studies about gendered divisions of labor. Recent series of work have used the lint cage of a clothes dryer to create images again relating personal history to larger critical issues about war and cultural violence. Today, age 83, Kelly teaches at USC and shows internationally. Her son, Kelly Barrie, now in his fifties and a working photographer, lives nearby.

It's great to know that Mary Kelly is still exhibiting, and thanks for addressing this important issue of maternal work and the subject of motherhood in art.

Best of luck with combining your two (or more?) jobs, namely making a new person and writing about art.

Another fascinating lesson Sarah, thank you.

Best of luck in the weeks ahead.. we will patiently wait for the next!