There is a hierarchy in the arts: decorative art at the bottom, and the human form at the top. Because we are men. —Le Corbusier and Amédée Ozenfant, 1918

Women have always collected things and saved and recycled them because leftovers yielded nourishment in new forms. —Miriam Schapiro, 1977

If you read last week’s substack about Holly Solomon, her gallery and her support of Pattern and Decoration artists, perhaps you asked yourself but what does their art look like? And today is about that. Of course there were many artists who operated under the P and D umbrella, many of them still alive, and their worked varied widely and shifted throughout their careers—we will cover several of them later in the 70s and 80s—but today I want to focus on a shining star of the movement, Miriam Schapiro.

Schapiro, born in Toronto in 1923 to Russian Jewish emigre parents, is a name you’ve heard from our time talking about Judy Chicago (she partnered with Judy to teach at the Feminist Arts Program at CalArts, which debuted Womanhouse, 1972, as its main project). What you probably couldn’t have guessed about her is that her maternal grandfather invented the first movable doll’s eye in the United States, or that her paternal grandfather sewed the arctic clothes for Admiral Perry and his explorers. She was sort of destined to be groundbreaking, or at the very least, interesting.

Miriam is one of the few artists we’ve talked about who was supported to be a professional artist by her family, her education, and her community. Her father was an artist who made his living as an industrial designer, and her mother was deeply supportive of Miriam’s artistic dreams. When the family moved to New York City, she sent Miriam to weekend classes at MoMA and to evening classes that were part of the Federal Art Project. Her parents supported her application to college to study art, and she matriculated with a BA, an MA, and then an MFA from the State University of Iowa, where she met and married Paul Brach. She taught children’s art and had various office jobs after college, but was a full time professional artist starting in 1955, when her early works were mostly abstract, landing her among the “second generation” of abstract expressionist artists popular in New York City. In the 1960s, the couple and their young son moved to California where Schapiro took a professorial job at UC San Diego, soon falling in with Judy Chicago’s mission to create a feminist art history and feminist art studio classes.

In Lucy Lippard’s 1973 essay, Household Images in Art, she pointed out that the Pop Art movements of the 1960s (think Lichtenstein, Warhol), borrowed heavily from images of domestic life mostly associated with women and women’s work. In the early 1960s, male artists moved into woman’s domain and pillaged with impunity, she explained, pointing out that never before had male artists been so interested in interior scenes, Campbell's Soup Cans, appliances and advertisements for groceries and staples of the home. Had women made art about these objects, she pointed out, critics would have derided it as just women making more genre art, while men taking on these topics was revolutionary. On the other side of the same coin, women who wanted to be taken seriously as artists were often afraid to make art about household objects, and avoided using “female techniques,” as she called them, sewing, weaving, knitting, ceramics, even the use of pastel colors (pink!)…they knew they could not afford to be called feminine artists, the implications of inferiority having been all too precisely learned from experience. Earlier in the century, artists like Pablo Picasso, Juan Gris and Georges Braques had used the technique of collage in the early years of Cubism (1912-1914ish), and were lauded as revolutionary geniuses for doing so. Of course, collaged works had long been made by women who did not so much consider themselves professional artists, but rather women with pastimes to round out their domestic experience of spending, for the most part, their entire lives at home. Many of these ancestors were women who were ignored by the politics of art....Schapiro would co-write in a 1977 text with Melissa Meyer. Now that we women are beginning to document our culture, redressing our trivialization and adding our information to the recorded male facts and insights, it is necessary to point out the extraordinary works of art by women which despite their beauty are seen as leftovers of history. Aesthetic and technical contributions have simply been overlooked.

Now that we women are beginning to document our culture, redressing our trivialization and adding our information to the recorded male facts and insights, it is necessary to point out the extraordinary works of art by women which despite their beauty are seen as leftovers of history. Aesthetic and technical contributions have simply been overlooked —Miriam Schapiro and Melissa Meyer

Lippard’s essay explained that thanks to the women's movement, artists were no longer as afraid to utilize aspects of their female identity in their art making, whether it be references to the domestic, to womens crafts, or to previous pastimes. They began shedding their shackles, proudly untying the apron strings—and, in some cases, keeping the apron on, flaunting it, turning it into art, she said.

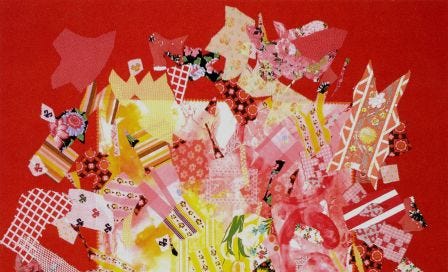

Schapiro was one such example, making art via her concept of femmage, defined by her as: a word invented by us to include traditional women's techniques to achieve their art: sewing, piecing, hooking, cutting, appliquéing, cooking and the like--activities also engaged in by men but assigned in history to women. Here we have Explode, 1972, as an example.

The vivid red surface is punctuated by a beautiful detonation of mixed collage and paint: fabric swatches, strips of lace, embroidered bits and small shapes of cut up pattern adorn a canvas also smeared by yellow gestures and a white rectangle at its center. The overall effect is of chaos and excitement, as if a sewing basket has exploded inside a retro, gleaming, pop-art red kitchen. The finished work, aside from reclaiming the scraps of feminine identity into her art, recalls another traditionally feminine act of creation: quilting.

The overall effect is of chaos and excitement, as if a sewing basket has exploded inside a retro, gleaming, pop-art red kitchen.

Schapiro went on to make many more large scale femmages, and continued to make art for the rest of her life. She also became an important and outspoken activist, forming, in 1979, The New York Feminist Art Institute, which sought to create a community of feminists via workshops, programming, exhibitions and classes. She died in New York in 2015 at the age of 91.

Brilliant read, thank you ❤️

Brilliant as always :)